The Story So Far

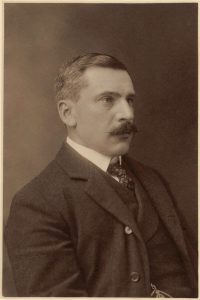

In 1897, three respected mining entrepreneurs announced that mine on Colebrook Hill would be greater than Mount Lyell.1 William Knox, William Orr and Herman Schlapp had helped create the massive Mount Lyell copper mine and had made their reputations in the early days of Broken Hill’s silver boom.2 They bought a big slice of the mine so that they could realise that dream.

The ‘Broken Hillionaires’ said that the Colebrook mine could be ‘more cheaply and expeditiously worked’ than Mount Lyell’s.3 The reason was a mineral, axinite, that was mixed with the copper ore. It was a natural flux for smelting.

They sampled the mine, but then drifted away. Maybe it was a fall in the price of copper. Many people never forgot their words and held onto the dream of a massive mine and smelter at Colebrook Hill.

The copper price stayed low, about £60 ($120) per ton until the middle of 1906. The price revived to £78 ($156) and that increased the share price of the Colebrook Prospecting Association.

This brought the Association out of hibernation. They held their first meeting in four years. Chairman Senator John Clemons gently led his audience. He mentioned the sampling done Herman Schlapp, one of the most respected metallurgists in the country. He had ‘proved the existence of large quantities of ore, which would average about 2 per cent of copper’. The directors believed that the mine would be payable ‘with the present prices of metal’.

Clemons dusted off the dream. He quietly took ‘the shareholders into his confidence’ and said ‘that if they had smelters at the foot of the Colebrook Hill the mine would be a very valuable one.’4

In a final touch, he noted that the Association had a large stock of forfeited shares worth thousands of pounds. He had gently fanned the embers of the dream and also showed the directors as steady thoughtful men, not the greedy thieves that ran many mines and fleeced their shareholders.

By the end of 1906 the copper price had risen another £30 per ton and Colebrook shares inched higher. The mine quietly reopened. Thomas J Williams returned as mine manager.5

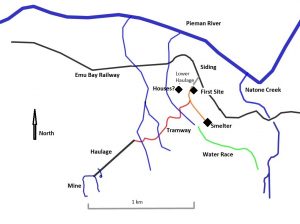

The market knew that something was afoot. The shares doubled in value.6 There were no official announcements when, in February 1907, the Association bought land for a smelter and started to survey the line of a tramway and haulage.7

The Announcement

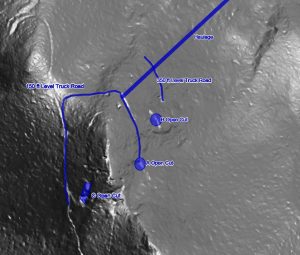

Finally, on 12 March 1907, 12 years after the lode was discovered, the directors of the Association announced that the dream would be made real. They would build a self-acting haulage on the Colebrook Hill and a tram that would connect the haulage to a smelter and the Emu Bay Railway.

The plant would smelt ‘at least 4000 tons of ore per month to a matte of about 50 per cent of copper’.8 The directors had ‘thoroughly satisfied themselves’ that the ore was rich enough to ‘ensure a fair profit, even with reduced prices for copper’.9 At 2 ½ per cent copper they could be profitable with a price above £60 – 65 ($120-130).10 The market copper price was about twice that. They were actually predicting huge profits.

They needed £12,000. Local investors gave it to them when they rushed the sale of forfeited shares.11 Work could continue, into a West Coast winter.

Opening Up the Mine

In March 1907, the Colebrook was a mine in name only. It had never produced anything more than a few tonnes of samples. Everything had to change for the mine to produce thousands of tonnes of good ore every week and transport it to the smelter.

The ore body was huge, ranging over the top 150 metres of the hill. But it was complicated. It was actually four different lobes that snaked through the hill and around each other.12 There were fissures of brightly coloured rich ore that promised wealth but much of it was lean.

Thomas Williams started to ‘open out’ the ore body. He and his men would form three open cuts with ore chutes to lower levels and waiting skips. Truck roads would contour around the hill to the top of the planned haulage.

March & April 1907 – Surveying

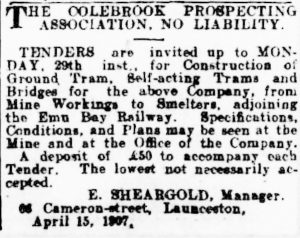

Work had begun on 27th February 1907. GA Moore, a consulting engineer, cleared the ‘heavy scrub … to make proper survey, and progress is rather slow’.13

He finished within a month. His plans and specifications were part of the tender.

May – Tendering

The tenders were too high. In late May, the directors decided to make ‘the line by day labour, with a few sub-contracts’.14

Two and half months had now passed before the first substantial work started. Moore’s 42 men began to clear the route of the haulage and tram. Miners dug into the iron-hard rock at the top of the haulage to form the footings for a wheelhouse.15

The Haulage

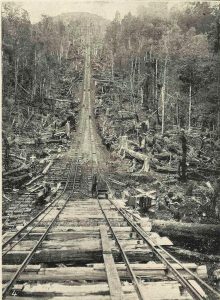

Colebrook’s haulage (also called a self-actor or inclined tram) was inspired by one at the Hercules mine near Mount Read.

It was basically two parallel tramways going straight up the side of the hill. Skips were attached to a single loop of thick steel rope. Gravity did all the work.

Filled skips at the top of the hill rolled down the ‘heavy’ side tramway. At the top of the haulage, the rope turned around a wheel to draw up the empty skips. Brake gear at the wheelhouse controlled the movement.

At the bottom of the haulage the full trucks were automatically emptied into hoppers by a ‘tippler’ before they turned and up the return tramway.

The haulage would take a year to complete.

June

Moore moved quickly. After only two weeks, his men had cleared and levelled 600 metres of the tramway. Timber was felled for the bridges over two deep creeks. A contractor started cutting sleepers.16

July

Winter struck after only one month of solid work. It would grip the site for three months.17 The tramway continued; more earthworks, piers placed for the first bridge, the second bridge started and further excavation at the haulage.18

Now Moore moved on to planning the smelter. Equipment was ordered from Launceston foundries. The directors announced that they would ‘make the mine in all respects a Tasmanian concern’.19 This was an empty promise. A ‘splendidly-elevated position’ was cleared for the smelter.20

August – The Big Cut

The first tramway bridge was finished despite ‘weather very bad for outside work’. A start was made on the ‘big cut’ where the haulage would tip into hoppers and to the tramway.21

September

‘Wet weather retarding work’.22 No.2 bridge was almost finished. Importantly work on the railway siding on the Emu Bay Railway started.23 Without it heavy equipment could not be moved onto the site or matte shipped out.

October – General Manager Appointed

An essential step was the appointment of a metallurgist for the furnace. Cecil Rae became general manager, with control over the whole operation and Thomas Williams at the mine. Rae had ‘extensive experience throughout Australia as metallurgist’. He had ‘been on the North Mount Lyell Company’s staff when smelting was being carried out at the Crotty’.24 Any link to its chaotic smelting performance must have been an embarrassment.

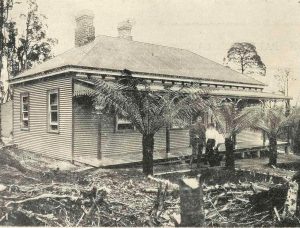

Rae’s energy, combined with better weather, meant that the pace of work increased. Clearing started for buildings and offices in a ‘commanding position to the west of the … smelter site’. There would be a general office, assay laboratory, general manager’s cottage, blacksmith’s shop and accommodation of the foremen.25

Another important work, a water race, started. It would supply the steam boilers and furnace cooling. A 1.6 km line was surveyed from ‘an excellent supply of water’ on Natone Creek.26

At the tramway, 700 metres of rails were laid and No.2 bridge was finished. Work had started on the ore bins at the bottom the haulage.27

In the mine, Thomas Williams opened up ‘some excellent copper ore, much better, in fact, than many people anticipated’. But it was not all good news. The rising tide of copper prices had turned. Undaunted, the directors were ‘still strong in their faith that the mine can be made to pay’.28

November

Rae walked into a fight that was going to take months to win. A neighbour with grazing land didn’t want the smelter and they wouldn’t agree on financial compensation. Even in the early 1900s pollution was an issue. Rae quickly abandoned the original smelter site.29 The smelter buildings were marooned.

Rae found a new site quickly enough, 400 metres south-east from the old one. Ever positive, the Association said that the new site had ‘many advantages, there being a good slope to the east with plenty of room available for a slag dump’.30 The move would not create ‘any great expense’ and caused ‘a slight delay’.31

The tramway formation was completed. More rails had been laid and more ballasting done. Half of the water-race had been made.

The siding on the Emu Bay Railway, ‘about the 35 ½ miles’ peg, was completed on 23 October.32 A short haulage would drag material to the tramway, which was about 40 metres above the siding. A steam winch was installed near the end of November.33 Now the main machinery could be received.

December

Almost 100 men were working and more were needed to open up the mine. The new smelter site was connected to the tramway by a 240-metre extension.34

The Association held a general meeting. Again, Clemons turned on the charm. He began by saying that ‘the board never withheld information from the shareholders’. Such honesty, and then he sketched out a very rosy picture. What few problems they had, were overcome.35

The tramway was almost complete and the ‘line for the self-actor had been finished’. Finished was a very flexible term. It would be another four months before it would operate. The cost of the tram and the haulage ‘exceeded somewhat the estimate’ because of the poor weather. Labour ‘cost 33 per cent, more than at any other period’. However, if they were ‘blessed with an ordinary summer … they were going to reap the benefit’.

The furnace bordered on a miracle. Not only had they ‘a site which offered every facility’. (There was no mention of the first site being abandoned and the tramway extended.) The furnace had ‘the latest ideas as to what was wanted in copper furnaces.’ And the Association had bought it ‘at a big discount’.36 Smelting would start ‘by April next … and this date would not mislead shareholders.’

Clemons praised Cecil Rae for ‘showing every desire to carry on matters as expeditiously and smoothly as possible’. 37

He addressed the 40% fall in the copper price. Clemons ‘could not take any other view than that they had a sound venture’. Smelting could be done ‘at a profit with copper at £60 per ton’. He repeated that ‘they had every reasonable and justifiable hope’ that they would ‘carry on smelting at a profit’. And, of course he mentioned the lucky charm of the mine, axinite, that wonder self-fluxing mineral.

January – 1908

The Mercury’s mining reporter produced an insightful article on the Colebrook mine. He went through all the standard stuff in detail. But for the first time the expected profit was given. ‘With copper at £60 per ton, the mine is considered sure to return £1,500 per month profit over all costs if 2 ½ per cent copper can be recovered.’

But there was a problem. He revealed that Schlapp had shown that the ‘copper return was nothing like 2 ½ per cent’. But in the end the reporter had to defer to the confidence of the Association’s directors.38 The only real test was to start smelting.

At the mine, work was mainly how ‘to handle the ore from the open cuts.’ The excavation for the smelter was nearly complete. Machinery for the haulage was being installed.39

The Furnace

On 10 February 1908, two sailing ships in Burnie off-loaded the furnace and more than 50 tonnes of machinery for the Colebrook mine.40 The cargo was transferred to the Emu Bay Railway.

The furnace was built by Martin and Co of Gawler, South Australia. It was 3 metres long and the height between the slag and feed floors was 7 metres. It was fitted with 12 tuyeres (nozzles to inject air into the furnace) on each side.41

The English air blower was capable of delivering 500,000 litres of air per minute at a pressure of 10 kPa. It would be powered by a 60h.p. vertical engine. ‘Steam would be supplied by two 40 h.p. colonial type multi-tubular boilers.’42

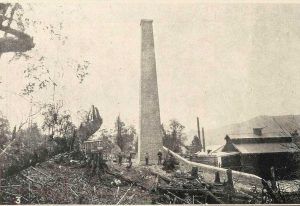

The Stack

25,000 Victorian bricks were railed to the mine in early January.43 James ‘Jim’ Coy, ‘an old West Coaster’, would build the stack, flue and brick the furnace.44 He completed the stack,18 metres high and 2 metres wide at the base, on 13 February.45 Apparently a record ‘on the West Coast, and, it is believed, for Australia’.

The flue, connecting the furnace and the stack, was completed in early March. Coy laid the last furnace brick on 11 April.46

February

The workforce was now 130 men, and they still needed more.47

The Zeehan and Dundas Herald was swept up in the excitement. They repeated the Association’s dream of ‘a large plant, one which will almost vie with the Mount Lyell Company’s’, that would be installed ‘if the smelting is successful’. They claimed that the ore was ‘from 3 to 5 per cent’ copper. The general manager, Cecil Rae, was ‘generally regarded as the right man in the right place, and he is pushing all construction work on in a praiseworthy manner.48

By the end of the month, the furnace shed, ore bins, a blower and one boiler were completed. ‘The furnace is being rapidly put together’.

It was not all great news. Most of the money raised in April 1907 had been spent. It went on;

Mining, …, £1990; trams, …, £4670; smelter, …, £3920; water race, £340; house, office, assay ditto, and sundries at mine, £730.49

The Association made a call of 6 pence (5c) per share for funds to complete construction and ‘to enable the company to start its smelting operations unhampered by debt’.

March – One Month to Go

Rae’s environmental problem came back. James Hill, the nearby landowner, was still not happy. He complained to the Zeehan Council. This exposed another issue. The Association hadn’t yet applied for a ‘Noxious Trade License’. And they couldn’t start without it.50

Another shock came. The share price dived to half of the high of 1907. The Association said nothing. The Mercury did. An article quoted information that had been consistently misrepresented for years. The sampling in the late 1890s by ‘the Knox-Schlapp people declared the whole mass taken in bulk to be unpayable. The assay of copper was about 1 per cent, with very little silver and gold’. The Mercury had ‘no doubt the best portions must be treated, and the poorer material thrown away’. The reason for the fall in the share price was ‘a rumour in mining circles, that at first the whole bulk is to be tried through the smelters’. This was ‘hardly conceivable’.51

Just two weeks from the planned start of smelting the mine manager, Thomas Williams, resigned.

The furnace was assembled, the ore bins completed and brickwork progressing quickly. At the haulage the rope, 32 mm in diameter, and weighing 4 ½ tons, had been positioned. 16 ore trucks were a few days away. All that was needed was to connect the water supply, ‘and it is ready to start smelting; about ten days more work in all’.52

April

1 April – Smelting was due to start but the haulage was not finished.53

4 April – 15 slag pots arrived at Burnie from Melbourne.54

6 April – The haulage was run ‘and proved very satisfactory’.55

9 April – The engine and blower for the furnace were run.

10 April – Two of the directors arrived for the blowing in of the furnace, which was expected on Monday 13th.56

11 April – A committee from the Zeehan Municipal Council inspected the site and spoke to local landowners to consider a Noxious Trades license for the smelter. AW Barnes and J Hill wanted compensation for any damage to their agricultural land. The committee recommended the licence and compensation if necessary. 57

The last bricks were laid at the furnace.

13 April – Smelting was delayed ‘owing to one or two small accidents on the haulage line’. A start was expected in two days.58

15 April – The haulage was run properly after the automatic tumbler had been delivered. However, this showed that the grips between the trucks and rope needed to be replaced.59 Blowing in was further delayed until Saturday 18th.60

At the mine, ore was being prepared at ‘A’ and ‘C’ open cuts. They were connected by truck roads to the haulage.

Monday 20 April 1908 – At 2pm the furnace was blown in. It smelted continuously for eight hours. It treated 83 tons of ore, ‘which is at the rate of close on 250 ton for 24 hours.’ The results with a new furnace were ‘beyond the most sanguine expectations’. The slag from the furnace ‘came away like so much bottle glass, indicating a low loss in copper in this direction.’61 Smelting had started without the usual opening ceremony that miners were so fond of.62

The smelter was stopped because of a leaking water jacket and for ‘a number of small adjustments’. Problems during commissioning are expected.63

The Tasmanian papers all called the smelter a success. The directors immediately advertised for 60 extra men to increase the production of ore for supply the furnace.64

1 May – Smelting was temporarily stopped for adjustments.65

4 May – The shareholders were surprised by a call of 6 pence per share, especially as the Association made no explanation.66 They reacted badly. The price of Colebrook shares dropped from 3 shillings 6 pence (35c). to about 2 shillings (20c) in a few days.67 There had been no further news about the operation of the smelter for at least a week. The directors returned to the mine.

9 May

Next – The Fiasco

Peter Brown – copyright 2020

1 Mercury, 1 December 1897.

2 Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 15 May 1897.

3 Mercury, 1 December 1897.

4 Examiner, 1 June 1906.

5 Examiner, 5 December 1906.

6 Examiner, 28 January 1907.

7 Mercury, 13 February 1907; Examiner, 5 March 1907

8 Matte is a mixture of copper, iron and sulphur which is then refined to metallic copper

9 Daily Telegraph, 12 March 1907.

10 Examiner, 20 December 1907.

11 Daily Telegraph, 21 December 1907.

12 GA Waller, Report of the ore deposits (other than those of tin) of North Dundas, Mines Department Report, 30 April 1902.

13 Daily Telegraph, 16 March 1907; Daily Telegraph, 5 March 1907.

14 Mercury, 25 May 1907.

15 Examiner, 11 May 1907.

16 Examiner, 8 June 1907.

17 Examiner, 23 July 1907.

18 Examiner, 9 July 1907.

19 Examiner, 17 July 1907.

20 Examiner, 23 July 1907.

21 Examiner, 20 August 1907; Examiner, 3 September 1907.

22 Examiner, 1 October 2907.

23 Daily Telegraph, 1 October 1907.

24 Examiner, 10 October 1907.

25 Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 16 December 1907.

26 Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 16 December 1907.

27 Examiner, 15 October 1907.

28 Mercury, 12 October 1907.

29 Daily Telegraph, 14 November 1907.

30 Daily Telegraph, 14 November 1907.

31 Daily Telegraph, 14 November 1907.

32 The North West Post, 13 March 1908.

33 Mercury, 27 November 1907.

34 Examiner, 16 December 1907.

35 Daily Telegraph, 17 December 1907.

36 Daily Telegraph, 17 December 1907.

37 Daily Telegraph, 17 December 1907.

38 Mercury, 17 January 1908.

39 Tasmanian News, 5 February. 1908; Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 25 January 1908.

40 North Western Advocate and Emu Bay Times, 12 February 1908.

41 Mercury, 22 April 1908.

42 Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 16 December 1907.

43 Examiner, 7 Jan 1908; Examiner, 10 January 1908.

44 Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 15 February 1908.

45 Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 20 February 1908; Examiner, 23 April 1908.

46 Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 14 April 1908.

47 Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 6 February 1908.

48 Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 15 February 1908.

49 Examiner, 28 February 1908.

50 Mercury, 5 March 1908; Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 1 April 1908.

51 Mercury, 12 March 1908.

52 Tasmanian News, 21 March 1908.

53 Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 2 April 1908.

54 North Western Advocate and Emu Bay Times, 6 April 1908.

55 Daily Telegraph, 15 April 1908.

[56 Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 11 April 1908.

57 Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 13 April 1908.

58 Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 13 April 1908.

59 Tasmanian News, 16 April 1908.

60 Examiner, 16 April 1908.

61 Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 22 April 1908.

62 Daily Telegraph, 20 April 1908.

63 Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 22 April 1908.

64 Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 25 April 1908.

65 Mercury, 5 May 1908; Examiner, 2 May 1908.

66 Mercury, 6 May 1908.

67 Mercury, 7 May 1908.

Dear Peter,

loved your articles on the story of the Colebrook Mine. Can’t wait for part 3. I did notice that the picture of Senator John Singleton Clemons in part 2 is a copy of the picture of William Knox from part 1. The picture of John Singleton Clemons can be found at ” biography.senate.gov.au>john-singleton-clemons”. They do look similar in appearance.

Tony

Thanks Tony for the comments and eagle eye. The photo has been updated now. Part 3 is such a bunfight that it is proving to be difficult to wrangle. It will be with you shortly. Peter