The wash in the creeks may carry gold, and lodes in the ridges be,

But the pyritic ore of the copper belt it pleases most to see;

Through the nameless scrub in the sun or rain we follow the luring quest.

And cut our way with our tomahawks where the badger makes his nest. (Paul Quinn)1

Mining is always a gamble, sometimes you get rich but mostly you lose your shirt. And sometimes the dice are loaded. Promoters’ self-serving enthusiasm can lead to wild exaggeration or even lies. A few good colours of metal in a rocky outcrop might be called the richest mine under the sun. Flooded with investors’ money, miners might buy machinery, build railways or furnaces without knowing whether the mine is good enough to repay the shareholders. Promoters might help themselves to the money in the investors’ pockets for a short but rich ride before the truth hits the fan.

Mines and metals go in and out of favour as prices rise and fall or investors rush in and out. The West Coast of Tasmania has ridden many wild booms and busts. The tin boom at Heemskirk, silver at Zeehan and Dundas and copper centred around Mount Lyell. Only a few mines lived long and fewer still profited their shareholders.

The Colebrook mine had its times of wild confidence and it had dark times too. Now its monument is the name attached to a forested hill behind the Rosebery Golf Course.

The Silver Boom

In 1882, silver was discovered at Pea Soup Creek on the west coast of Tasmania. But investors weren’t interested in this remote undeveloped region.2 That changed in 1888.

Broken Hill, in the desert in western New South Wales, became the byword for incredible wealth and profits. Investors couldn’t get enough shares in its silver mines. So they went searching for the ‘next Broken Hill’. Thousands of kilometres, and a climate away, the old discovery in a swamp on Pea Soup Creek was woken from its slumber. Prospectors combed the forests, swamps and wind blasted plains for more silver riches. Almost 100 square kilometres was taken up as mineral leases.3

At Zeehan and nearby Dundas everyone needed a sprinkle of the magic dust of Broken Hill. Some wanted its experienced mine managers and they all wanted its investors. Its entrepreneurs were drawn to the wet forests and swamps of Tasmania. This included the royalty of the Barrier Ranges like the Broken Hill Proprietary Company’s directors Bowes Kelly and William Orr and metallurgist Herman Schlapp. They invested in up and coming mines.

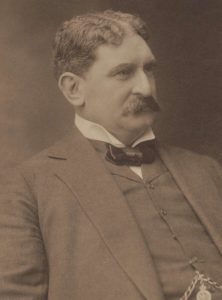

Most of the people who came to the West Coast were poor men hoping to make rich discoveries. Paul Patrick Quinn and William John Hodge were typical. Both had grown up on farms in the Tasmanian Midlands. Quinn was educated ‘at his own fireside and under the wise training of his father and mother.’ He wandered to New South Wales but left with a damaged ankle after a life threatening accident. Then he chased tin on the East Coast of Tasmania. At the end of 1890 he went to the West Coast for silver. He remained a hardworking but unlucky prospector all through the boom, only sustained by small finds of gold and contracting.4

William Hodge was the son of a blacksmith. He also came to Dundas in its early days.5 Around 1891, he took a claim near the top of a tall hill that overlooked the Pieman River near Mount Black. His was one of many.6 They were attracted by outcrops of rock with tell-tale stains of metals. But few did more than chip away a few samples. Only one prospecting association did much work when it sank a shaft into the rock near the top of, what was called, Lewis Hill.7

The collapse of the Bank of Van Diemen’s Land on 3 August 1891 clearly marked the end of the silver boom as a global recession struck. The crazy speculation at Zeehan and Dundas ended. It drove out the speculators and fraudsters. Only the very best mines survived. Many promising finds stayed undeveloped. Hodge, like many others, abandoned his lease.8 9

The crash did not drive out seasoned and wealthy investors. Canny entrepreneurs looked for undervalued and unloved mines. In the very shadow of the Bank of VDL collapse, Bowes Kelly and William Orr came to Zeehan to look at a struggling gold mine at nearby Mount Lyell.10 Metallurgist Herman Schlapp recognised it as a potentially great copper mine. By 1893 Mount Lyell ore had been smelted at the recently closed Argenton Smelters of the Broken Hill Ore Dressing and Smelting Company. Even under ‘’ridiculous conditions” the ore smelted beautifully and produced a few tonnes of very rich (65%) copper matte.11

Money poured into the Mount Lyell mine for railways, haulages, smelting works, and the thousand things needed to build a big new mine and smelter in remote wilderness. Before the furnaces produced a single tonne of copper it had generated at new boom on the West Coast. The speculators, investors, prospectors, store owners and publicans returned.

Bright Colours in the Rain

Paul Quinn and William Hodge returned to the bush with renewed optimism. In December 1894, they pitched their camp ‘in the pelting rain, on the top of a ridge that runs … from the Ring River … towards the Pieman.’ This was Lewis Hill near Hodge’s old lease. They broke open an outcrop with a ‘hard, iron stained surface’ and were encouraged by ‘a strong smell of sulphur’.

They left for ‘hammer, drills, and dynamite’. The first blast ‘tore large lumps out of the face of rock, and heard them falling hundreds of feet down the steep hillside.’ Quinn ‘picked up piece of shiny stuff …We never saw anything like it before’.

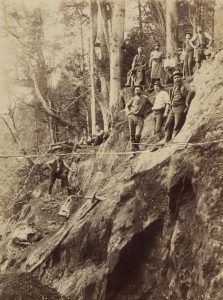

The government geologist, Alexander Montgomery, was perplexed too but the rock contained copper. Quinn recalled that Montgomery ‘said more flattering things about the show than I would care to write down here’.12 The steepness of the hill, by now known as Natone Hill, was a bonus, it provided the ‘most excellent facilities for proving the lode by tunnels.’13

Quinn and Hodge dug. By February 1895 they had exposed 30 metres of the lode and it kept on going. A three-metre-deep adit improved with ‘every foot driven upon it’.14 The rock was bright with the colours of copper pyrites, blue copper ore, and native copper. A sample contained 9 percent copper, much higher than Mount Lyell.15They claimed three mineral leases.

They now encountered the first hurdle to success for many mines – poor access. There were no railways, roads or tracks to the mine. For the moment six kilometres of new pack track would be enough but they needed money.16

Floating the Mine

In April 1895, the Colebrook Prospecting Association was formed in Launceston.17 The discoverers took half of the shares. And they named the property Colebrook after Quinn’s old neighbourhood in the Midlands.18 At this early stage the newly formed association claimed that it was ‘a large lode that simply requires opening up’.19 With shareholders and their money they could now start work.

Their section (mineral lease) was cleared. A tunnel was driven into the side of the hill and cut seven metres of ‘solid pyrites body, showing a fair percentage … of copper, gold, and silver’.20 It seemed amazingly rich. Essays of 12 to 20% copper were quoted.21 At this early stage the indications were good. But perhaps not enough to justify the Zeehan and Dundas Herald’s claim that ‘there can be no doubt that the Colebrook is an exceedingly big show, and its similarity to the pyrites of Mount Lyell promises well for its richness’.22

Encouraged, the prospecting association asked their shareholders to again dig into their pockets.23 Alex Peoples was appointed mine manager.24

The discovery at the Colebrook mine had fired an interest in the whole area. Soon the whole hill and surrounds were claimed. The name Colebrook was splashed around the other leases; North Colebrook, South Colebrook, East Colebrook, Great North Colebrook, Extended Colebrook, etc.25 26

Within a year of the discovery, the lode had been traced across the full width of the Colebrook section. The optimism became detached from reality. Low assays ‘need cause no alarm to shareholders, for it would not be reasonable to expect an immense ore body like the Colebrook to give a high assay from every bit of stuff tried.’27

With the general enthusiasm of a boom it was easy to turn logic on its head.

Mount Lyell, the only other body of the same description as the Colebrook in Tasmania, does not give high assay returns outside of the rich vein, … many assays made from Mount Lyell stuff in its early days that gave no results at all28

Then they added another level of wild optimism when it was claimed that the ‘the Colebrook lode has this advantage over the Mount Lyell that … the axinite which forms so large a part of its formation is a flux of a peculiarly valuable character’. 29 30

Driven by optimism and generally encouraging developments, the Colebrook mine was steadily opened up by the manager and ‘two, or sometimes four, men’.31 A new mining manager, WN Fitzgerald, was appointed in August 1896.32

Soon the miners found that the lode ran across the broad brow of the hill and deep into its heart. The Colebrook PA bought the surrounding sections to claim the continuation of the lodes and for better access from all sides of the hill.33

The Colebrook was going well but Quinn ‘did not get a job on his own show, and was not fairly dealt with in other respects.’ He and Hodge put their efforts in their nearby discovery at the Clifton mine.34

Broken Hillionaires – The West Coast Triumvirate

May 1897 marked when the inevitable rise to greatness of the Colebrook mine was guaranteed. William Knox, William Orr and Herman Schlapp bought half of it.35 They brought ‘large sums of their own capital’, ‘long and varied experience of Australian mining … together with shrewd financial end administrative ability, and the highest standard of mineralogical and metallurgical skill. The West Coast community greeted their involvement ‘with universal satisfaction’.36

William Orr visited the mine for 10 days. ‘The chief thing we have to prove,’ said Mr Orr, ‘ so far as we can tell at present is whether the bulk of the material can be concentrated successfully. If we once demonstrate that, then we have a pretty smelting proposition. The ore is beautifully tractable and will be very easy to smelt’. The pulses of shareholders and speculators must have raced when Orr linked his approach to concentrate the ore before smelting to ‘the second biggest copper mine in the world’, the ‘great Anaconda mine in America’.37 Orr’s message contained a coded secret, the ore was probably much poorer than previously stated. But not everyone picked it up.

The experienced entrepreneurs began to systematically prove the richness and size of the mine, guided by ‘the eminent metallurgist’, HH Schlapp. He ‘makes very few mistakes … In fact, Mr Schlapp’s whole Australian career, apart from his American experience, stamps him as a metallurgist of the first rank’. With this guidance ‘it is any odds on the Colebrook blossoming into a producer of copper on a mammoth scale, together with gold and silver in certain quantities’.38 They also brought in their hand-picked mine manager, Richard Williams.39

They were systematic and brutally honest. By 1898 the mine proved to have ‘very large quantities’ of ore that could be ‘very cheaply mined by open-cast workings’. But ‘it is too poor in copper and precious metals to smelt by itself’. Richer ore had to be found or a way of concentrating copper content of the current ore.40

Work continued at a pace. 30 men dug the many shafts, drives, benches and open cuts that slowly brought the hidden depths of the lode into the sight of these experienced men.41 In November 1898, a quicker way to reveal the heart of this big lode was arrived at when a powerful drill started the first of five bores.42

Twilight on the Hill

Promoters loved to spread good news and make it better than it really was. The flipside was that they held bad news tight. It isn’t clear when the mighty Broken Hill entrepreneurs departed the mine. Probably late in 1899. The bores had been completed. The results must have been poor, some indications were that it contained less than 1% copper.43 The ‘mighty triumvirate’ had moved onto Queensland mines. The Clipper newspaper took aim at HH Schlapp. ‘It would have been better if he had stuck to metallurgy instead of racing round after shows that were not there.’ ‘The Curtain and Davis, the Colebrook, the much boomed copper show in Queensland (all associated with Schlapp), and other claims have proved a sad frost’.44

The Colebrook PA avoided these facts and suspended work ‘pending the completion of the Emu Bay railway to Rosebery’. It closed its London office.45 Operations basically stopped in March 1900 when the manager, Richard Williams, left to ‘a large copper mine in North Queensland’.46

For the next six years the mine spluttered in and out of life. Various schemes came and went but all were half hearted.

When the Emu Bay Railway arrived near the mine in June 1900 the Colebrook PA should have been excited about the chance to get its ore transported cheaply. It wasn’t. It toyed with the idea of sending its ore to smelting works planned nearby.47 Samples were sent to the Mount Lyell Company but the ‘heavy cost of transit, makes this impracticable.’48

It wasn’t until 1901 that there was any real thought about linking the mine to the Emu Bay Railway. There was talk of an aerial bucket conveyor running to the north of the hill to meet the line. 49 But the strong intentions announced in the newspapers amounted to nothing. Some tunnelling was done between March and November 1901 by underground manager Thomas Williams, brother of a former manager. 50 The Colebrook PA formally shut the mine down in November 1902.51

Some samples were sent to London in July 1903 for tests by three different concentration processes. The results of one were good, the other two were not reported.52 The mine was left to be reclaimed by the forest. The darkest time came in September 1906 when the Colebrook PA had to fight to keep its leases because it hadn’t done any work in four years.53

The Long Wait is Over

The dawn came at the end of 1906 when the copper price improved dramatically and an optimistic mood returned to the Colebrook PA. And with it a determination unseen since 1899. In December, Thomas J Williams was reappointed as mine manager.54

In January 1907 rumours started to flow about a smelter being built.55 The director of the prospecting association had recently said that ‘if they had smelters at the foot of the Colebrook Hill the mine would be a very valuable one’.56 In February land was bought for a smelter, approval obtained for smelting from a local authority and work started on a tramway.57

Finally, in March 1907, after 12 years, the directors of the Colebrook PA announced that the lode at the top of the hill would be mined and smelted. At last the shareholders would receive some income from their long held investments.

The association would ‘erect a plant capable of reducing at least 4000 tons of ore per month to a matte of about 50 per cent. of copper’. This meant building a ‘self-acting tram from the north side of the mine to the foot of the Colebrook hill’, connecting it by a tram to a smelter site and building a smelter near the Emu Bay Railway.58

With this strong plan and work already started, the association needed a lot of money. It offered 33,500 shares to market and local investors rushed the offer.59 Their share price surged to levels unseen for many years. The long wait was almost over.

Peter Brown – copyright Mountainstories.net.au

Part 2 – Smelting in the Forest

[1] Wombats were also known as badgers, Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 19 July 1898.

[2] Charles Whitham, Western Tasmania; a land of riches and beauty, Davies Brother Hobart, 1949. p 109.

[3] Geoffrey Blainey, The peaks of Lyell, Melbourne University Press, 5th ed., 1993, p 51.

[4] Mount Lyell Standard and Strahan Gazette, 15 December 1897.

[5] The Advocate, 19 June 1940.

[6] North Dundas Mineral Charts, map 126A 1893 -1911 – Mineral Resources Tasmania

[7] A. Montgomery, Report on the progress of the mineral fields in the neighbourhood of Zeehan, the Mackintosh River, Mount Black, Mount Read, Mount Dundas, Stanley River and Mount Heemskirk, Geological Surveyor’s Office, Launceston, 15th May, 1895, Mineral Resources Tasmania, Report OS118, p 23.

Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 12 October 1897.

[8] North Dundas Mineral Charts, map 126A 1893 -1911 – Mineral Resources Tasmania.

[9] A. Montgomery, 1895.

[10] Blainey, p 57.

[11] Blainey, p 61.

[12] Daily Telegraph, 27 December 1895.

[13] A. Montgomery, Report on the progress of the mineral fields in the neighbourhood of Zeehan, the Mackintosh River, Mount Black, Mount Read, Mount Dundas, Stanley River and Mount Heemskirk, Geological Surveyor’s Office, Launceston, 15th May, 1895. Daily Telegraph, 1 July 1895.

[14] Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 5 February 1895.

[15] Daily Telegraph, 27 December 1895.

[16] Launceston Examiner, 2 April 1895.

[17] Launceston Examiner, 18 April 1895.

[18] Mount Lyell Standard and Strahan Gazette, 15 December 1897.

[19] Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 22 May 1895.

[20] Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 15 August 1895.

[21] Launceston Examiner, 25 October 1895; Daily Telegraph, 20 July 1895.

[22] Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 28 August 1895.

[23] Daily Telegraph, 2 August 1895.

[24] Zeehan and Dunas Herald, 15 August 1895.

[25] Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 14 October 1895, 16 November 1895.

[26] North Dundas Mineral Chart 1893-1896 – Mineral Resources Tasmania.

[27] Daily Telegraph, 27 December 1895.

[28] Daily Telegraph, 27 December 1895.

[29] Daily Telegraph, 27 December 1895.

[30] Daily Telegraph, 28 March 1896.

[31] Daily Telegraph, 28 March 1896.

[32] Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 17 August 1896.

[33] Daily Telegraph, 1 December 1896.

[34] Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 12 October 1897.

[35] Mercury, 19 May 1897.

[36] Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 15 May 1897.

[37] Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 28 May 1897.

[38] Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 28 May 1897.

[39] Mount Lyell Standard, 17 July 1897.

[40] Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 27 August 1898.

[41] Daily Telegraph, 28 January 1898.

[42] Mercury, 23 November 1898.

[43] Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 12 April 1901.

[44] Clipper, 21 October 1899.

[45] Daily Telegraph, 1 June 1900.

[46] Examiner, 29 March 1900; Mercury, 18 December 1900.

[47] Daily Telegraph, 1 June 1900; Examiner, 29 March 1900; Mercury, 1 June 1900; Examiner, 30 November 1900.

[48] Daily Telegraph, 29 November 1901.

[49] Examiner, 28 May 1901; Daily Telegraph, 12 August 1901.

[50] Examiner, 30 May 1902.

[51] Daily Telegraph, 28 November 1902.

[52] Mercury, 20 July 1903; Examiner, 13 January 1904.

[53] Mercury, 13 September 1906.

[54] Tasmanian News, 5 December 1906.

[55] Examiner, 30 January 1907.

[56] Examiner, 1 June 1906.

[57] Mercury, 13 February 1907, Examiner, 5 March 1907.

[58] Daily Telegraph, 12 March 1907.

[59] Daily Telegraph, 21 December 1907.

For a young country we have so much forgotten history.

Good read

Too right, thanks Peter