Many people have become lost in the Tasmanian high country. These days it is bushwalkers. In the past it was bush workers; prospectors, snarers, cattlemen and explorers.

A few were ill-prepared. Most were unlucky. Even the most prepared and experienced people can be caught when the weather suddenly changes to bring wind, rain or snow. Sometimes injury or misadventure strikes.

Some chose to try to walk to safety. Others waited and hoped. Hope that their overdue return was soon noticed by friends and loved ones. Hope that the searchers set out quickly. And hope that their chosen little shelter in the vast landscape would be found before they succumb.

There would always be a search. In the past it was the community; friends, family, locals and the nearest police. Now dedicated search and rescue professionals and trained volunteers willingly put themselves at risk in the hope of bringing a missing soul back to safety.

Over the next two blogs we tell the story of two searches that are separated by 110 years.

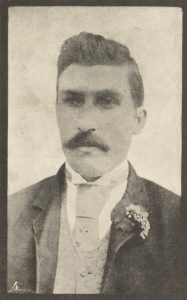

The Missing Man Yates1

110 years ago, Edward Yates became lost on the Western Tiers near Mole Creek. Simon Cubit wrote about ‘the missing man Yates’ in the second volume of his Mountain Stories.2 He painted the picture of the search and concluded that it was both a tragedy and properly mysterious.

The newspaper reports of the day are fascinating. They were written in the language of the day. They told the unfolding story with all its twists and turns. Sometimes they informed and sometimes it was wild speculation.

On Monday 5 July 1909, ‘about half a dozen men left Mole Creek for the Western Tiers, to search for cattle that on previous attempts they had been unable to bring down. Having no success, they decided to stay up over night, and try again next day.’3

According to the Examiner, ‘one of the party, E Yates, refused to stay, and left the others as they were making for the hut, taking the right direction for the track down, and telling those who enquired if he was sure he could find the way that he “could find it in the dark.”

Yates’ companions returned the next night but Yates had not. They immediately formed a search party. On Wednesday morning ‘A party of 17 started early … to look for him, but could find no trace of the wanderer’. Later in the day ‘A much larger party, (100 persons) provisioned for several days, started’. After just two days, the newspapers reported that ‘Little hope is entertained of finding the unfortunate man alive, as he had no food the second day, and carried no overcoat with him – a very necessary protection from the intensely cold weather at present experienced on the mountains.’

Late on the night of Friday 9 July there was hope when ‘some of the search party came down to report that … they had found what is supposed to be his (Yates’) foot prints’.4

The position and direction of the first foot prints found led the searchers to believe that Yates had not found the entrance to the track, and, instead had attempted to force his way strait down the face of the mountain, and perhaps injuring himself, or became too weak to force his way through. In consequence of this theory the greater number of searchers have devoted the last three or four days to a thorough examination of the face of the mountain all around where the mark were found. At the same time parties have been scouring the plains on top, starting from the Western Creek, Caveside, and Circular Ponds, as well as from Mole Creek5

They might have found Yates’ footprints but not the man. One week after Yates’ disappearance, the Examiner reported;

Quite a gloom has been cast over this part owing to Mr. Edward Yates, a local resident, being lost on the Western Tiers. As he has now been out five days, and the weather in that locality has been bitterly cold and snowy, grave fears are entertained for the unfortunate man’s safety… Trooper Davis, of Chudleigh, has been out in the search party throughout, and has displayed praiseworthy energy.6

Despite the gloom, there were still about 300 people searching.7

Even eleven days after Edward Yates became lost;

large numbers are bravely struggling on in search of the wanderer, in spite of cold and foggy weather. On the face of the mountain virgin forest of such density that in many places it could be penetrated only by crawling on hands and knees has to be encountered, and on top vast stretches of unknown, treeless, and trackless plains, intersected in many places by those strange rock formations known as “ploughed fields.” 8

Then the search swung from the front of the mountain, the most likely area, to further back on the Western Tiers. The community was so desperate for hope that they would follow any clue, no matter how unlikely.

Messrs. Miles Brothers, who have been back about 18 miles from the front, between the two Fisher Rivers, hunting, had hung two carcases of game on a tree, and on returning to remove them found both gone, and footprints around showing plainly that a human hand had taken the meat. Speaking of the foot marks, it would be well to remark that Edward Yates was a big man, and wore an unusually large boot. It is stated that others who were up there on the Monday night when Yates was lost heard someone coo-eeing far back from the front.

Mr. Miles states that … on this occasion he not only saw the footprints, but one evening, when going around his snares, he heard a peculiar, far-away sound, that he compared to someone singing loudly. This would seem to indicate that Edward Yates has gone in that direction, for it is well known to residents of Mole Creek that he was in the habit of singing heartily when walking alone.

This report defied logic but it was taken seriously. Yates would not be singing or coo-eeing by that stage. Against all the odds some felt that ‘he may still be recovered alive.’ The desperate optimism of these hopes shows how much Yates’ disappearance touched the community.

The searchers continued their futile hunt in dreadful weather.

Much sympathy is felt with, and admiration expressed for, the indefatigable searchers, not only on account of the physical hardships they are enduring, but also because of the inconveniences they will feel through the extended loss of time, which to labourers and farmers must be rather serious.

The searchers were jumping at shadows and now thought that they were on the edge of finding Yates. 16 days after he became lost;

The searchers, who were forced to come down from the mountains on Sunday to obtain provisions, returned early yesterday morning. They report that all the party are agreed that they are on the tracks of a lost man, whether the lost one be Yates or some other unfortunate. They are apparently getting very near to the one they are following, for the tracks are very fresh, and they are expecting to come up with him at any time; in fact, so near did they seem to be, and so eager were they to accomplish their humane task, that they continued searching until they had exhausted their provisions, and were obliged to make a forced march to the accommodation house to avoid famishing.9

Despite earlier giving up home on finding Yates alive after two days (and a single day of bad weather will kill), it was a month before the Weekly Courier wrote;

Reluctantly the various parties who have been in quest of Mr. E. Yates have been compelled to relinquish the search. Severe snowstorms swept over the summit of the Western Tiers for many days, covering the mountain to the depth of several feet. Some of the searchers who were last to retreat narrowly escaped with their lives, having been caught in a dense fog, with no compass to guide them, and got up their waist in snow. Among the party were the Yates brothers and Will Howe. 10

In November, hope was briefly revived in a final cruel act. A bottle was found at the Third Basin of the Cataract Gorge in Launceston. It;

contained a note, which was dated 13/8/09 and read as follows:—”Bushed near Lucy Long on the Western Tiers; fell and broke my leg; starving; help.—(Sgd.) Yeates.” … The note has every appearance of being genuine, and seems to Indicate the fate the unfortunate man.11

It was soon pointed out that there was no water course connecting Lake Lucy Long and the South Esk and that a glass bottle would not survive the rocky river journey down from the Western Tiers to Launceston.

The properly mysterious disappearance of Edward Yeates is still remembered in the names of locations near Lake Mackenzie. The efforts of his many searchers, largely volunteers in large numbers but also police, were ultimately futile. But it didn’t stop them searching in dreadful conditions holding onto any hope that he would be found alive. Or that his body would be recovered for his family to friends to mourn. Some searchers risked losing their own lives in the hunt for the Missing Man Yates.

The next blog takes us 110 years later.

Copyright Ian Hayes & Peter Brown 2020

1 The spelling of his last name is either Yates or Yeates. The features around Lake Mackenzie use the spelling Yeates.

2 Simon Cubit, Mountain Stories Vol. 2, Forth South Publishing, Hobart, 2017, p 36

3 Examiner, 9 July 1909

4 Examiner, 10 July 1909

5 Examiner, 17 July 1909

6 Examiner, 12 July 1909

7 North West Post, 13 July 1909

8 Examiner, 17 July 1909

9 Examiner, 21 July 1909

10 North West Post, 5 Aug 1909

11 Daily Post, 5 Nov 1909

Fantastic, poor man.

Such a sad tale. Thank you for sharing, though.

Great reading, but a sad outcome