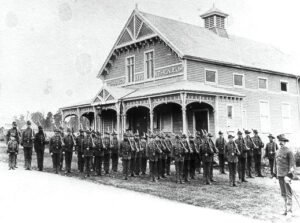

In May 1900 Major Frederic Hughes (1858–1944) might have been fighting the South African War. Only a month earlier the Waratah detachment of the Wellington Rifles had drilled in the main street ahead of camp in New Town, Hobart, where four of their number were selected for the Imperial Bushman Contingent.1 But it is possible that Hughes, a high-ranking Victorian citizen-soldier, didn’t go because he wasn’t needed in Transvaal.2 Instead of blasting the Boers he was ensconced in Waratah’s Bischoff Hotel drawing tenders for another combat operation. Frederic was going to blow a large hole in Savage River.

Reigning mayor of St Kilda, mining investor, company director, Hughes was ‘a man’s man who mixed easily and enjoyed a range of masculine interests’.3 Good thing, because it didn’t get much more butch than humping gelignite up and down the precipices that separated Waratah from the Savage. ‘TENDERS are invited’, he wrote,

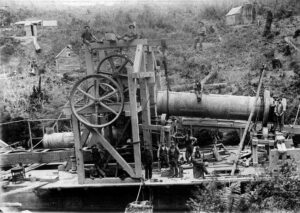

‘returnable to me on or before noon on SATURDAY June 2, for making tunnel 22 feet long, 6 feet high and 8 feet wide, and also a dam across the Savage River at a point near the 19-Mile Creek. Full particulars to be obtained from EF NICHOLSON, 19-Mile Creek, or DAVID JONES, District Surveyor, Waratah. FG HUGHES, Crawford’s Hotel, Waratah.’4

The purpose of the tunnel

I thought Hughes wanted to blast a simple diversion tunnel to divert the stream so that a dry section of riverbed was exposed to prospecting for osmiridium.5 You needed a dam to divert water away from the site of your tunnel while you built it. I had a vague memory of reading that Savage River had been diverted. Wanting to check some loops on the river for diversions, in February 2024 Ian Hayes and Eddie Firth and I mounted an expedition, climbing over the steep divide between the Nineteen Mile and Savage. They were like mountain goats. The pair soon scaled the equally precipitous country on the other side of the Savage, establishing that no diversions had been driven through the loops. The loops in question turned out to be about 50 metres apart, too much rock to tunnel or channel through to divert the river.

Hughes’ dry loop

However, as soon as Ian read the Hughes advert, he recognised that he planned not so much a tunnel as a gelignite placement site. Then I rediscovered the reference to the Savage being diverted. It was in the caption for a series of Weekly Courier photos of osmiridium mining on Savage River and Nineteen Mile Creek in 1921. One photo showed a man standing amidst a waterfall on the Savage ‘at a point where Major Hughes turned the stream 18 years ago’. The old bastard! He did divert the Savage, but where? In fact Hughes was reported to have ‘turned’ about ¾ of a mile of river to work it for osmiridium.6

I had made the mistake of searching the map for existing loops in the river, that is, loops through which the Savage River still flowed. As usual, Ian was more forensic than that. He started looking for dry loops in the river—and there it was, a tiny blue line cut off from the Savage at both ends of its loop. The Hughes diversion was still in place 124 years later. He’d killed part of the river.

To ground zero

In March 2024 Ian and I set off down the old overgrown track to Caudrys Reward. Overcoming the cutting grass, bauera and fallen banksias, we reached the stone-walled water features of Flea Flat, where the growing tea trees and dogwoods had left a pleasantly empty understory. Across the creek we climbed to the saddle of the divide. Down the other side we experienced next level steepness, one that I conquered on my fundament, tobogganing down the slope as a small avalanche.

At the bottom the Savage was a stagnant pond, that is to say, the dry course of the loop had received a little water from a feeder creek which had nowhere to go. It was clear that the loop was just as it appeared on the map, severed from the flowing river at both ends. As we approached the eastern end of the dry loop we heard the roar of Savage River. In winter it jammed logs into the neck of the loop, and as we climbed the logjam the scene of the Hughes blast spread out before us. There was the waterfall created by the 20-metre-wide gash in the high wall of rock. Even in a dry Indian summer the Savage was crashing through it.

Ian’s belief that Hughes’ seven-metre tunnel was only dug to set gelignite plugs inside the rock wall was now vindicated. On the other end of the loop we found a bank of slate and shingle that was probably the dam built to stop the Savage flowing back on itself.

(Top) The blast site, showing the logjam in the eastern neck of the loop, the waterfall pictured in 1921 and the blasted-out wall section. (Above left and right) The waterfall from the eastern and western necks of the loop. Nic Haygarth photos.

Perplexity

Two things were not making sense. Where were the osmiridium workings which justified the effort and expense of blasting a great hole in a river? Away from the blast and dam sites, there was not a skerrick of obvious human activity along the dry bed of the river. Occasionally a suspicious-looking stump or rockpile hove into view but there was nothing convincing. Surely Hughes’ syndicate didn’t fund this great diversion without first establishing the payload that would result! Everyone knew that mining folk, hard-nosed businessmen, weren’t like that.

The bed of the old Savage River on its ¾-mile dry loop. Nic Haygarth photos.

The other thing bothering me was why they were working so high up the Savage River. Didn’t Hughes’ syndicate know that the source of the osmiridium on the Savage River system was the serpentine on Caudrys Hill (aka Bald Hill)? Well, no, of course they didn’t, because in 1900 Government Geologist WH Twelvetrees hadn’t told them yet. Bill Caudry hadn’t even started lode mining the stuff on his hill. In 1914 when Twelvetrees reported on the osmiridium he recalled those early prospectors on the Savage, concluding that ‘The mineral in the Savage River obviously came from the Nineteen Mile’, that is, the osmiridium on Caudrys Hill washed down the Nineteen Mile Creek into the Savage River.7 In 1921 Assistant Government Geologist Alexander McIntosh Reid concurred.8 Yet the Hughes syndicate worked way above the Nineteen Mile’s confluence with the Savage. What exactly was driving them?

The Kiwi connection

Dredging. Hughes and his backers were attracted to the Savage by its potential for dredging. The advent of the Whyte River Dredging Company to bucket dredge gold and osmiridium out of the Whyte River was a trans-Tasman technological transplant.9 Some miners believed that if it worked well in Otago it was a shoo-in across the ditch. However, the Whyte River Dredging Co took seven years to achieve almost nothing, its £3000 dredge finally being dismantled in 1905.10 In the meantime, while it was absorbing countless calls on shares without actually being proclaimed a failure, the Whyte River dredge inspired dredging claims for the same metals on Savage River. It might have been possible to tow a dredge into the mouth of Savage River, but much of the stream above there would have proven too narrow and rocky for a dredge.

Hughes’ British syndicate reportedly held 16 km of the Savage under dredging lease at the time of the diversion blast.11 It is possible that they wanted to dredge the bed of the Savage exposed by the diversion, attacking an ancient metal-bearing river bed buried beneath it. To do so would mean assembling the dredge on site, a monumental task given the transport difficulties. Available information is sketchy, to say the least. The Savage River above the Nineteen Mile was forgotten as a mining field when the Caudrys Hill hypothesis took hold. Only the blast site and the dry loop of the Savage bear witness to earlier excitement.

Hughes goes into battle

Frederic Hughes eventually saw military combat. The word ‘savage’ probably took on a different meaning for the now colonel after, at the advent of World War One, he was appointed to the First Australian Imperial Force to command the 3rd Light Horse Brigade. Fifty-six years old and lacking battlefield experience, Hughes was placed in the unenviable position of learning the hard way when in August 1915 he was ordered to attack Turkish positions at The Nek, Gallipoli. Some of the tragic scenes that followed were depicted in Peter Weir’s movie Gallipoli. The men who mounted a bayonet charge in support of the New Zealand attack on Chunuk Bair were decimated. Four waves of Light Horsemen who charged the trenches were also cut down by Turkish fire.12 Hughes ordered the fourth wave to stand down, but with his communication misunderstood they hastened to their deaths like their predecessors. Saddled with much of the blame for the disaster, Hughes was repatriated to Australia and retired with the rank of major general.13 To wonder if things might have ended differently had Hughes served time in South Africa rather than toying with the Savage is to indulge in hypotheticals. Similarly, we may never know for sure why the major moved a river.

Copyright Nic Haygarth 2024

1 ‘The Transvaal War’, Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 24 April 1900, p.2.

2 Peter Burness, The Nek: a Gallipoli tragedy, Exisle Publishing, Auckland, New Zealand, 2nd edn., 2012, p.28.

3 Peter Burness, The Nek, p.28.

4 ‘Tenders’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 30 May 1900, p.3.

5 When I wrote On the ossie: Tasmanian osmiridium and the fountain pen industry in 2017 I thought Hughes planned a diversion tunnel and must have confused Savage River with its tributary Nineteen Mile Creek. Where would you find loops on the Savage that were only seven metres through? It turned out there was one.

6 ‘Mining’, Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 30 July 1900, p.2.

7 WH Twelvetrees, The Bald Hill osmiridium field, Government Survey Bulletin, no.17, Department of Mines, Hobart, 1914, p.11.

8 Alexander McIntosh Reid, Osmiridium in Tasmania, Government Survey Bulletin, no.32, Department of Mines, Hobart, 1921, p.53.

9 ‘Whyte River Gold Dredging Company’, Launceston Examiner, 31 August 1899, p.2.

10 ‘Mining: dredging at Whyte River abandoned’, North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 20 June 1905, p.3.

11 ‘Bischoff and district’, Mercury, 22 June 1900, p.4.

12 ‘We remember Frederic Godfrey Hughes’, Imperial War Museums: lives of the First World War website, https://livesofthefirstworldwar.iwm.org.uk/lifestory/7303133, accessed 24 March 2024.

13 Peter Burness, The Nek, pp.24, 135–39.

Fantastic Story

Excellent read, never heard of it before

& I have lived in Tasmania for almost 82 years .

Thank you for posting .

Brilliant story Nic ! What happened to the Whyte River Dredge?

A fascinating read Nic. A detective story with a twist in the tail.

Thanks for taking the time to capture this Nic.

An amazing and perplexing story to say the least.