Water was everything at the Mount Bischoff Tin Mine. Rain pelting on Waratah meant tin ingots shipped to London and coin rattling in shareholders’ pockets. The ‘Bischoff mist’ ensured that cassiterite (tin ore) was separated from its host rock. On the mountain itself, water from the Summit Dam snaked its way down the slopes, supplying in turn the sluice-boxes of the Slaughteryard Gully, Brown and White Faces. At one stage seven waterwheels churned the Waratah Falls simultaneously, driving the stunning blows of stampers and the hydraulic whirrs and whooshes of automatic troughs and sieves.

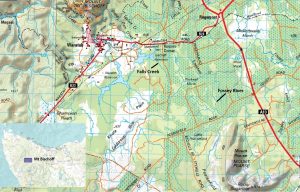

Except for the Cairns hinterland in northern Queensland, Tasmania’s west coast mining field is the wettest in Australia. Yet during summer the Mount Bischoff and other mines would at times shut down for want of water. In 1880, when the rich Brown Face of Mount Bischoff promised vastly increased production, Mount Bischoff Co Mine Manager Ferd Kayser took steps to enlarge the water supply. He chose a site on Falls Creek, a tributary of the Waratah River to the east of the township of Waratah. The Stone Dam on Falls Creek and connecting water race were finished at the end of 1881. ‘With this result’, Kayser later wrote, ‘reservoir-building became the order of the day’. 1

The largest of the Falls Creek Dam, the bluestone-faced Penneys Dam (aka Bischoff Reservoir). Nic Haygarth photos.

Over three years the Mount Bischoff Co built five dams on Falls Creek. However, the dry summer of 1882–83 still crippled work at the Mount Bischoff Co sheds, prompting the company to look further afield for water. Oddly, the man who came to Kayser’s aid was his greatest opponent. Despite being long estranged from the company, its founder and ex-director James ‘Philosopher’ Smith asked his grub-staked prospector WR Bell to investigate diverting water from the Hellyer River system to the company’s purposes.2 Bell reported back that he believed three-quarters of the flow of the upper Hellyer River (the Fossey River) could be carried by open race and some fluming (a box timber section of race used to maintain height across low ground) into Falls Creek, the stream the Mount Bischoff Co had already dammed as its major water storage.3

Chairman of Directors William Ritchie thought the Coldstream River would answer the company’s needs better, but in the winter of 1884 24-year-old surveyor William Sale vindicated Bell’s exploratory work.4 When Sale completed his survey of the 6.5-km-long aqueduct in January 1885, mine manager Ferd Kayser envisaged it taking only four months to build, enabling the company to benefit from the next winter rains.5

Construction actually took a full year. The contractor was another Kayser antagonist, James Pearce—whose very profession of publican had made him an enemy of the tee-totalling autocrat.6 The pair had clashed over the sale of alcohol at Waratah’s New Year ’s Day sports.7 Nevertheless, in February 1885 the directors accepted Pearce’s tender, and all excavation was done by the end of July, leaving only the fluming to be built and put in place and the water to be diverted into it.8

Pearce’s Hotel had a dirt floor. Money was so tight that at closing time Alice Pearce was said to sift the floor for fallen sovereigns.9 Perhaps then the conditions in the tent camps along the line of the Fossey system were no hardship for James Pearce through the autumn, winter and spring of 1885. It’s not difficult to imagine the men in the tent camps, frequently soaked to the skin and knee-deep in mud, snaring for extra food and fighting off nightly incursions of devils and quolls looking for food. It is unknown whether the timber flumes were constructed on site or even what timber they were cut from. King Billy and pencil pine don’t grow as low as an altitude of 650 metres, the approximate height of the Fossey system, but there was plenty of eucalypt to work with.

Timber fluming on the Fossey Aqueduct, courtesy of Liz Harris.

The cost was heavy. For surveying and excavation alone the Mount Bischoff Co forked out £2179—and the expense didn’t stop with flume construction.10 While water races basically just needed to be kept clear of fallen vegetation, with the occasional wash-out to fix, flumes were high maintenance. Nearly all flumes, trestles and stringers along the Fossey aqueduct were replaced after only nine years.11 The Mount Bischoff Co was less inclined to maintain the system in the early 1900s when it incurred heavy expenditure refurbishing the whole Mount Bischoff processing operation. In 1905, for example, the Fossey aqueduct was going to be ‘patched up, and may then last another year or two’.12 Yet the hydro-electric operation introduced in 1907 needed just as much water as the water-driven one it replaced, ensuring that the Fossey kept flowing into the reservoirs until at least World War One (1914–18).

By that time the mine was declining rapidly. Between 1891 and 1921 the average grade of Mount Bischoff ore fell from 3.0% to 0.3%, while through the same approximate period production dropped by about 48 tons of tin per year.13 Perhaps by the 1920s less water was needed, because the Fossey scheme was abandoned and quickly fell into disrepair.14

Nic Haygarth – 2021

1 HW Ferd Kayser, ‘Mount Bischoff’, Proceedings of the Australasian Association for the Advancement of Science (ed. A Merton), Sydney, 1892, vol.IV, p.349.

2 James Smith to WR Bell, 11 June 1883, NS234/2/1/9 (TAHO).

3 WR Bell to Smith, no.179, 12 June 1883 and no.190, 22 June 1883, NS234/3/1/12 (TAHO).

4 William Ritchie to James Smith, 19 June 1883, NS234/3/1/12 (TAHO).

5 ‘Mount Bischoff Tin Mining Company’, Daily Telegraph, 30 January 1885, p.3.

6 For Pearce see ‘Obituary’, Examiner, 10 July 1912, p.7.

7 ‘Waratah’, Telegraph, 8 January 1883, p.3; James Pearce, ‘Waratah Sports’, Launceston Examiner, 25 January 1883, p.3; ‘Waratah’, Daily Telegraph, 29 November 1883, p.2.

8 ‘Mount Bischoff Tin Mining Co Limited’, Launceston Examiner, 29 July 1885, p.3.

9 Richard Pike, Pioneers of Burnie: a sesquicentenary publication, 1827–1977, the author, 1977, p.32.

10 ‘Mining meetings’, Daily Telegraph, 1 August 1885, p.3.

11 ‘Mining meetings’, Launceston Examiner, 1 August 1895, p.2.

12 ‘Mining meetings’, Daily Telegraph, 1 February 1885, p.3.

13 HK Wellington, ‘Mount Bischoff Company Tin Smelter’; in DI Groves et al, A Century of Tin Mining at Mount Bischoff 1871-1971, pp.86–87. The period Wellington referred to regarding the drop in tin production was 1885 to 1922.

14 In 1926 when the Mount Bischoff Power Station was preparing to power not only the company’s own plant, but the suction dredge (aka the pontoon) in the North Bischoff Valley and the Bischoff Extended plant, consideration was given to spending £1000 to recommission the Fossey (Minutes of the Mount Bischoff Tin Mining Co, 12 August 1926, NS911/1/34 [TAHO]). A new lease from the VDL Co would also have been needed.

Great article Peter.

I covered the leasing of this water race from the VDL Co. in my book, “Fires, Farms and Forests”.

I wanted to write more but didn’t have the material and it was a bit off topic. I tried to get drawings and photos without success, so I am very pleased to see the photos in your blog.