Mineral prospectors were not defined only by their successes. Their failures were necessary learning experiences. Mining is a fickle business, with success depending not only on the presence of a rich and enduring ore body but other factors such as market prices, accessibility and, sometimes, the public imagination.

Lincolnshire-born prospector WR (William Robert) Bell (1830–1911) is remembered for his discovery of the Magnet Silver-Lead Mine west of Waratah. From the balcony of his grand 1892 home, Glen Osborne, standing alone on a hill above Burnie, Bell could have watched the Magnet ore being shipped for processing at Cockle Creek near Newcastle, New South Wales.

Over a period of about 40 years Magnet produced more silver than any mine at ‘Silver City’, Zeehan or Tullah—but it didn’t fund Glen Osborne. That was paid for by two of Bell’s failures, which he and his business partner James ‘Philosopher’ Smith sold for £3000 each before the mines fizzled out.1 It wasn’t a swindle. The sellers were conscientious, ‘experts’ pronounced the mines good and buyers with Broken Hill silver on the brain took a risk and did their money.

(Left) Glen Osborne, Bell’s 1892 home on the hill at Montello, Burnie; and (right) the view of the port of Burnie from its balcony (photos N Haygarth).

Bell learned about mining’s trials and tribulations as early as the summer of 1867–68, which he sweated out with pick, hammer and tap on a hill high above the upper Mersey River, chasing a narrow blue stain through the rock. He had come to Tasmania from South Australia, where copper was powering the local economy. Now he kept a farm at Latrobe with his nearly-blind ex-convict uncle, ducking out when he could to explore the untracked hinterland for minerals.2

Bell knew another man who lived the same way, James Smith of Westwood near Forth. As similarly-aged, church-going, single men, hungry for knowledge, used to subsistence living and committed to finding minerals, Bell and Smith had much in common.3 Both struggled to identify minerals in their early years, suffering from the absence of local geological expertise and investors to help them in their quest.4

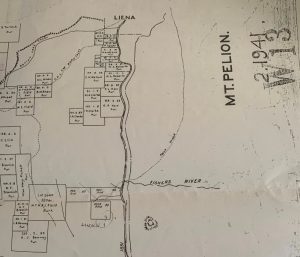

(Left) Mount Pelion mining map showing the pack track crossing the Mersey, and the silver and copper leases around Copper Mine Flat (opposite ‘Fishers River’ [Martha Creek]); (right) the Mersey River looking south about where the pack track crossed it, showing the hill (background, centre) into which Bell drove his adit (photo N Haygarth).

It appears that by April 1867 Smith and Bell discovered copper together on the Dove River, where Smith applied for two mining leases.5 One month later, while prospecting around the Mersey River near Gads Hill, Bell found some promising indications of mineralisation and built a hut on a benched platform about 40 metres west of the river.6 Near it was a permanent tributary of the Mersey, in which he would have followed upstream ‘colours’ of what he thought was copper. He must have continued panning up a steeply falling tributary of that stream and, at about 510 metres above sea level, Bell drove an adit into the base of a rock face. In March 1868, with his funds exhausted, he arrived in Launceston with specimens of not just copper, but lead, antimony and ‘native asphalt or bitumen’ from the Chudleigh area, hoping to attract investors.7 Bell found no takers for his unproven mineral shows and returned to his uncle’s farm. Decades of field work and all the lessons of business lay between him and financial success as a prospector.

Finding Copper Mine Flat

Bell’s discovery was at the edge of the Mount Read Volcanics, the highly mineralised Cambrian volcanic belt containing many of Tasmania’s richest mines—at the contact of the Ordovician limestone and sandstone and Tertiary basalt.8 The copper show has been erroneously referred to at times as ‘Little Bell’, a reference to WR Bell’s unrelated namesake George Renison Bell. That the site is also wrongly plotted on such maps attests to its early discovery and long abandonment.

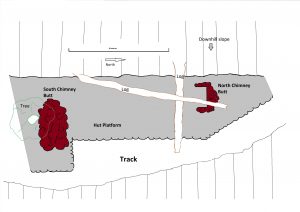

A survey of two mining leases enabled Peter Brown to fix fairly accurate co-ordinates for both Bell’s hut and his copper show. Wading the knee-deep Mersey River from the Mersey Forest Road, Peter and Ian Hayes were stunned by what they found in the scrub and bracken fern above the river. The generously-sized chimney butt that first came into sight was dwarfed by a monolithic one nearby. The chimney remnants were set on a built-up hut platform about 15 metres long. The eastern or lower side of the platform had a neat stone retaining wall. Someone had gone to a lot of trouble here.

A large building with two rooms and two chimneys didn’t tally with Bell’s solitary struggle, but a check of newspaper and mining records confirmed later occupation of the site. Bell abandoned Tasmania for the mainland in 1871, but by then two blocks had been leased by new parties at his copper show.

(Left) Monolithic chimney butt at the southern end of the hut platform (with 2-metre rule); (right) part of the 15-metre-long retaining wall supporting the platform.

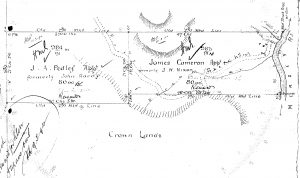

Crop from the survey of Pedley and Cameron’s silver reward applications, 1891, showing the position of the Copper Mine Flat hut on the pack track on the western side of the Mersey River. The track crosses the ‘stream’ and heads up hill to Bell’s workings.

Bell’s hut at the so-called Copper Mine Flat was still standing and recently occupied in 1887.9 It would have been used again by the advance party trying to find a route for the railway line between Mole Creek and Zeehan in 1891 but, understandably, the engineers who followed them labelled their route along the western bank of the Mersey River impassable. There were also further lease applications at this time in the wake of the Broken Hill boom.10 The economic collapse of 1891 may have dulled these applicants’ dreams, since all leases had long since lapsed by the time of a copper reward lease application in 1901. None of these people appears to have advanced the case for payable mineralisation on the upper Mersey.

Interpreting the hut platform

On a second visit to the hut site, Peter, Ian and Nic cleared the platform of vegetation and were again impressed by the enterprise of the builders. Clearly the site was old. No tree stumps remained from the hut construction, and about 35 centimetres of humus had had time to settle on the rectangular platform. Ian identified ancient nails with a square, chisel-like profile found near the smaller chimney butt/hearth, suggesting that it was earlier than the monolithic one, which sported nails of a more familiar profile. Ian’s examination of the great chimney butt revealed that its hearth was orientated obliquely across the platform, meaning that it did not line up with the hearth at the northern end. This meant that there were two separate hut sites meeting roughly end on. The one with the smaller chimney butt and the ancient nails was probably Bell’s 1867 hut. The hut with the great chimney butt and more modern nails was probably built by a later party.

Finding Bell’s copper show

Now for Bell’s mine, 600 metres away, which Peter had plotted from the survey map. Large expanses of bracken fern indicated that the hillside above the hut had been cleared, and we hadn’t gone far when Ian stumbled upon a long steep trench. Bell’s workings, however, were known to be high on a hill on the southern side of the unnamed Mersey tributary. We crossed the stream and sidled across the steep hillside, on which the spindly regrowth again suggested regular burning off and clearing up until recent times. The precipitous stream Bell had followed up hill became a series of cascades and waterfalls in the vicinity of his workings—but where were they? A huge rock like the prow of a ship stood above us. The Mersey River was a distant ribbon gleaming through the base of the forest. In such steep country we knew we were looking for an adit driven into the hill, but it would take just a landslip or a fallen eucalypt to obliterate the evidence.

(Left) Ian and Peter at the adit; (right) view of the Mersey River from the hill near the adit (photos N Haygarth).

Then Ian had his Picnic at hanging rock moment. Gazing up the cliff above the Ship Rock, he muttered something about not having been up there and began to climb. Pipes of pan were lilting somewhere as he slowly disappeared beneath the sun-drenched brow of the hill. However, unlike Miranda and the other schoolgirls in Peter Weir’s movie, Ian was snapped out of his trance by a gaping hole in the base of the cliff. An adit less than 10 metres long was home to a desperate tree fern rooted in some putrid water. The blue vein of mineralisation identified by Peter on the tunnel wall smacked of similar desperation.

Bell’s legacy

‘One of Tasmania’s explorers’. That is the epitaph on WR Bell’s headstone, but it was also written on his prospecting portfolio. His career included a boating trip down the Arthur River from the Hellyer River junction to the ocean, testing the headwaters of the King and Gordon Rivers as well as the VDL Company lands from Robbins Island to the Middlesex Plains. Bell had to explore Tasmania’s geology in situ in order to learn how to find the colony’s mineral wealth, and his Mersey copper show was an early part of that process. Trudging back and forth along the rough Dawson’s Track from Latrobe, over Mount Claude to his remote copper show seems grim today, but Bell’s appreciation of geomorphology (the study of landforms) and his reminiscences of scenery, great waterfalls, thylacines and even a kangaroo fight observed while prospecting make it clear that the bush offered significant compensations for his hardships.11 While the Magnet Mine closed in 1940, the skarn deposit of the Kara Scheelite and Magnetite Mine, around which Bell skirted in the late 1870s and early 1880s, is still worked today as a testament to the mining lessons he learned in the Tasmanian highlands.12

NIC HAYGARTH Copyright 2021

1 Bell received £2000 from the sale of the Bell’s Reward Mine and £1000 from the sale of the Discoverer Mine, both of them being on the 13-Mile line of lode south-west of Waratah. See agreements dated 3 February and 15 June 1891, NS234/3/19 (TAHO) and Nic Haygarth, ‘”The Broken Hill of Tasmania”: the rise and fall of the 13-Mile silver-lead field, westernTasmania’, Journal of Australasian Mining History, vol.13, October 2015, pp.102–10.

2 For Bell generally, see Nic Haygarth, ‘Richness and prosperity: the life of WR Bell, Tasmanian mineral prospector’, Papers and proceedings of the Tasmanian Historical Research Association, vol.57, no.3, December 2010, pp.203–35.

3 In 1882 Bell chaired religious meetings at Waratah (‘Missionary meeting at Waratah’, Launceston Examiner, 15 November 1882, p.2; and Sicklemore to James Smith, 7 March 1882, no.390, NS234/3/11 (TAHO).

4 Smith’s ‘copper’ from his 1862 discovery at Copper Creek, Lea River, was judged to be very poor iron by a local ‘expert’ (WR Bell to James Smith, 28 January 1862, no.33, NS234/3/1 ([TAHO]). See our previous blog.

5 James Smith to WR Bell, 9 April 1867, no.413 (letter held by Peter Smith, Legana).

6 ‘Copper at the Mersey’, Cornwall Chronicle, 1 May 1867, p.5.

7 ‘Minerals’, Mercury, 14 March 1868, p.2, quoting the Launceston Examiner.

8 KD Corbett and PM McClenaghan, A review and interpretation of the Lower Palaeozoic geology of the Que River-Sheffield area, with particular reference to the Cambrian volcanic sequences, Tasmanian Geological Survey, Record 2003/17, Mineral Resources Tasmania, 2003, p.28.

9 ‘The missing men’, Tasmanian, 9 April 1887, p.28. Two men, William Walters and William Wilkinson, were stranded at the hut for a week, unable to ford the Mersey River. They made use of the 10 lbs of flour inside the hut.

10 A reward lease was one issued at a peppercorn rental to the first discoverer of a mineral in a particular area.

11 See Nic Haygarth, ‘Richness and prosperity’.

12 See Nic Haygarth, ‘Mining the Van Diemen’s Land Company holdings 1851–1899: a case of bad luck and clever adaptation’, Journal of Australasian Mining History, vol.16, October 2018, p.93.