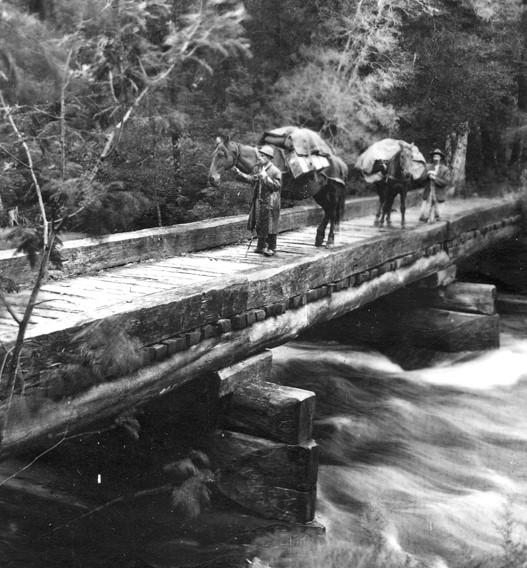

You’d think it would be hard to lose a bridge across a major river like the Forth. Sloane’s bridge was substantial, 35 metres long and with 200 metres of formed approaches. But it disappeared a long time ago.

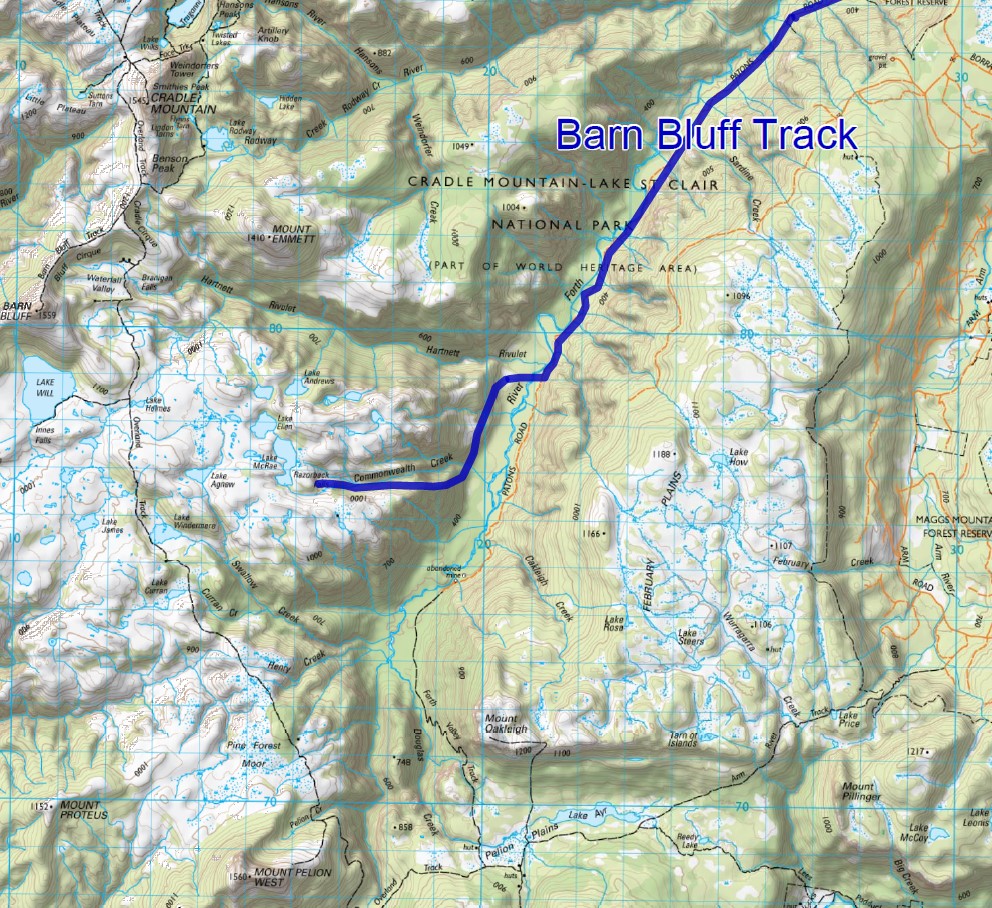

Sloane’s bridge was built in May 1902 as part of a track from Gads Hill near Liena to a mine high above the river near Barn Bluff. The Barn Bluff Copper, Gold and Silver Company started to explore at Lake McRae in 1900 but by 1901 it was hamstrung by the long winding access along the Mole Creek Track. The mine looked promising but needed more equipment and supplies. The promoter said, that it was with ‘not the slightest doubt in my mind … the premier mine in Australasia … the biggest property under the sun’.[1] The solution was the Barn Bluff Track. It would improve access by being shorter and avoid the high exposed plains of the Mole Creek Track by sheltering in the Forth River valley.

The route of the track was chosen by Surveyor William H Paton (hence the name that applies to the road along the Forth River) and Richard Broomhall (Public Works Department Overseer). They made some changes to a route found by bushman Harry Andrews.[2] Part of the track and the bridge were supervised by Alexander Sloane, an accomplished overseer.[3]

Despite all the promises and the new track, the Barn Bluff mines were abandoned by the end of 1903.[5] There were revivals of the mine and the track but mostly they just decayed and were overgrown. Late in 1916 the Barn Bluff Track was cleared to the bridge and a new track was cut south along the bank of the Forth River to the Pelion Plains.[6] The Barn Bluff track became an under-used side track and the bridge got little traffic.

What happened to the bridge over the years is not clear. It is likely that it existed for many years. It did give access to a high plain just to the west of the bridge which had been cleared for feed paddocks for horses for the Barn Bluff mines. The Wolfram miners may have used it for this too but they also cleared a paddock nearer to their mine (their workings are still visible in the upper Forth at the end of Patons Road).[7] There is a tantalising suggestion that the bridge was still in place in 1954 but most timber bridges do not last that long without maintenance.[8]

Ian Hayes and I had heard rumours about the bridge so we began a hunt for it and other old places along Paton’s Road. It wasn’t clear how much of the bridge remained. We made the long reconnaissance trip up Paton’s Road to the Wolfram mine. Most of the road is in good condition the bridges and culverts are gone. Then we did some searching of the archives and on aerial photographs. There was no sign of the bridge but we decided that it would be a little south of the confluence of the Hartnett Rivulet and the Forth River. The river was fairly low when we made our next trip to look for the bridge.

Ian Hayes takes up the story.

Our return to the upper Forth river area happened yesterday on a wet day, however luck was on our side once again. Sloane’s bridge was located pretty much exactly as our research had indicated it to be.

We dropped off Patons road at the confluence of the Forth and Hartnett, I was searching on the Eastern side of the Forth and Peter West. Peter got wet fording the river to gain access to the opposite bank but had good country at foot, alternatively I wasn’t too keen on getting wetter than I was. The going on my side was ordinary, I hear a shout from Peter to come across – my reply was that you better have something positive or I am staying on my side.

Peter persuasive blurb had a hint of – he might be onto something, I wades the river and said this better be good. Photos attached tell a thousand words and the approaches to the bridge and the Barn Bluff pack track still remain visual 100 plus years on.

The long eastern approach is a wide mound that leaves the bottom of a steep hill and curves across the flat wet floodplain to the river. It is dotted with stumps, probably from felling the timbers for the bridge. The eastern bank has been washed away and none of the bridge work remains there. The two bridge supports in the middle of the river are also gone. The western side is different.

The first sight is a lot of moss and twigs covering the ground but below that are the few remains of this substantial bridge. There is a large squared log that had been the footing for the western end of the bridge. A short section of the deck lay collapsed in front of it, covered by a mat of moss.

Closer up there are the bolts, long spikes and plenty of shorter iron spikes used to nail the deck down.

Closer up there are the bolts, long spikes and plenty of shorter iron spikes used to nail the deck down.

A levelled path runs west from the bridge and then melts into the ground. There are also plenty of old stumps on this side of the bridge too. Stumps often outlast the structure that they were used to construct.

This is the remains of the old bridge on an old track that was built for a mine that lasted only a few years and, despite all the promises, yielded nothing. It is melting back into the country that it was cut into, just a smaller reminder of the human history of the beautiful country.

Peter Brown and Ian Hayes

Copyright MountainStories.net.au 2018

[1] Daily Telegraph, 11 March 1901,

[2]Examiner, 8 March 1902

[3] Advocate, 10 August 1949

[4] Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery, Launceston

[5] Mercury, 19 January 1904.

[6] Tasmanian Archives, PWD 24/1/3, Correspondence and associated Papers relating to Construction and Development of Tracks, including Tourist Tracks, Generally and in Municipalities – Deloraine, 9/131-33, Track: Lorinna to Lake Ayr and Mt Pelion Mine , 29 January 1917.

[7] Boyer, P, The Upper Forth Valley, Post-Settlement Historical Outline, TasForests, September 1989, p 39 – 43

[8] Regional Geology Survey – Lorinna, July 1954, Mineral Resources Tasmania, UR1954_091_107

The Mystery of the Missing Publican

There is a story that has been passed down through generations. A mystery that has been discussed in camps and argued in many places. It is the mystery of the disappearance of the Rosebery publican, Thomas Connolly, in 1901. An experienced prospector, Connolly left his hotel to walk to a mine near Barn Bluff. He never returned. Most thought he died some were near Lake Windermere but rumours of murder and absconding, and many other unnamed options, abounded.

By chance Connolly’s body was found 9 months later on the February Plains near the Mole Creek Track. He was more than 25 kilometres beyond his destination. To get there he would have walked along a busy track and past two huts on the Pelion Plains full of workers from the nearby mines. Naturally there were more rumours about what had happened to Thomas Connolly.

Ian and I were both fascinated by the mystery of Thomas Connolly. We’d both read some stories and found articles in the newspapers of the day. Finally, we decided that we had to work out what had happened. It was a long journey where we followed Connolly’s footsteps and found a good explanation for both why he perished and why so far from his camp. Along the way Thomas Connolly’s life story came out. And what a life he led.

We’ll unfold the long story of Thomas Connolly in a series of blogs.

Peter Brown copyright MountainStories.net.au 2019

Hi, very nice website, cheers!

Thanks for the kind comments. Come back soon, or subscribe, there will be more blogs shortly, Peter