I hear the thresh of the spiteful hail,

And I feel the lift of the wind beneath,

The forward heave and the lightning lurch

And the shuddering gasp like a living thing,

As we crouched in the heel of the tempest’s grip

High on the shoulder of Hamilton!1

– Marie EJ Pitt, ‘A West Coast silhouette (Tasmania)’

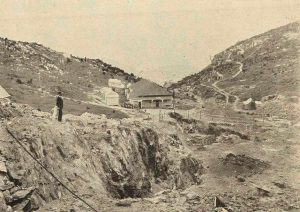

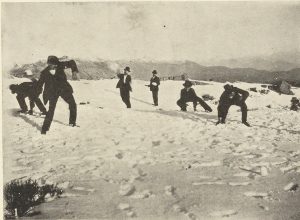

Stephen Spurling III, the photographer whose languid black-and-white images helped popularise the Gordon River, got his first taste of the West Coast as a surveyor’s assistant in 1896. Many years later he recalled life on the mining frontier of Mount Hamilton (then known as Mount Read), near Rosebery, and in particular events at its nerve centre, the Mount Read Hotel, a weatherboard and split timber establishment about 900 metres above sea level.2 The ‘thresh of the spiteful hail’ would have been an everyday reality there. Perhaps only the old Ben Lomond Hotel under Stacks Bluff rivalled it for altitude.

Many miners boarded and received their midday crib at this pub, mud streaming from their blueys, beards, boots and leggings as they entered the dining room. Blasting by the Mount Read Mining Company boomed across the mountain, on one occasion even lobbing a lump of metal through the hotel roof, scattering card players. Transport was equine. Spurling recalled how the bar-room piano was hauled up the mountain strung between two sturdy horses on the only connector to the outside world—a 16-kilometre-long, 2.5-metre-wide pack-track.

Almost as hefty was the pair of Irish bouncers who kept peace at the bar and discouraged bolting debtors. Their boss and the proprietor of this ‘wild west’ masculine realm was Sarah Goldie, who commanded unusual respect. After all, she was vice-president of the Mount Read Cricket Club.3 By her name Sarah’s three-year-old daughter Eliza Reid (Read) Goldie was rock-bolted to the mountain for life.4 Sarah Goldie had an even more visceral connection to the West Coast, embracing one of the staples of mining lore: she had married a prospector who was swindled out of his fortune.

The find and the ‘swindle’

In 1891, when Launceston and Hobart jockeyed for the West Coast mining trade, the Mole Creek and Zeehan Mineral Prospecting and Exploration Company (MCZMPEC) was formed in Launceston to find mineral lodes which the anticipated West Coast railway might deliver to market. Coal, silver and copper were discovered in the Pelion-Barn Bluff region, today contained by the Cradle Mountain-Lake St Clair National Park, but no payable lode resulted. By 1893 the directors were keen to wind up the company, relinquishing a mining lease on the slopes of Mount Read.

Cue the Goldies. In the 1870s and 1880s between 20,000 and 30,000 people selected land in the ‘Great Forest of South Gippsland’, as part of the rush to Australia’s so-called ‘Wet Frontier’, that is, the rainforests covering fertile pasture.5 Gippsland was seized by a dairying boom centred on supplying fresh butter to the metropolis of Melbourne, and also exporting it to Britain. Victorian government subsidies for dairying raised the rate of forest clearance.6 Among the selectors were Scottish immigrant Thomas Goldie and his Goulburn-born bride Sarah McGrogan, who farmed and kept a boarding-house at Bena, South Gippsland.7

How exactly the Goldies graduated from the wet frontier to the wild one on Mount Read is unknown. Many Gippslanders looked to start afresh in Tasmania. For Thomas Goldie, however, buried riches did not refer to dairy pasture. In December 1893 he secured a licence for a hotel at Mount Read, suggesting that he already had a mining claim there.8 The Zeehan-Dundas silver-lead field was depressed, but Goldie stores at both Mount Read and Dundas supplied the mining folk who remained.9

In the winter of 1894 Goldie uncapped a lode of pyrite bearing gold and silver on the forfeited MCZMPEC lease. Believing Joseph Will, head prospector for that company, to be the lessee, Goldie informed him of the discovery. Will did not disavow Goldie of his mistaken belief. He re-pegged the claim and, promising Goldie a share, made haste to Launceston. When the MCZMPEC directors declined to revive the claim, Will found other investors with whom he floated the Hercules Gold and Silver Mining Company.10

The Goldies, like other bush hoteliers, were regarded as friends of the miner who would turn no-one away without a full load of tucker. In this case Thomas should have been a doubter. His reward for his trust—or naïveté—was a 2% share in the new company. A settlement reached in court after he sued Will and others netted him 2750 shares in all—a still measly 5.5% interest.11 The Hercules Co also placated him with the job of mining manager.12

Thomas Goldie disappears from history

Thomas Goldie’s death only a few months later in 1896, at the age of 36, cleared the way for others to claim the Hercules discovery.13 More than 200 mourned at his grave, among them a local correspondent who recorded that

poor Goldie has gone to his long rest just as the clouds were beginning to lift after years of trouble, but his many good and kindly actions will be treasured for years to come fragrant in the memory of the numbers he has assisted.14

That cloud-lifting updraft may have been the rise in Hercules shares that very day from 8 shillings to 19 when the lode was cut in the mine’s main tunnel. By 1913 the Hercules had paid £36,323 in dividends—but the future got brighter yet.15 Improvements in ore separation and recovery by Electrolytic Zinc guaranteed the Hercules decades of operation, during which it produced metals to the estimated value of $1 billion. Whether Sarah and her child benefited, or whether the widow sold her small interest in the mine out of necessity, is unknown.

Sarah Goldie mourned her husband dutifully.16 She battled on alone at Mount Read for about eighteen months before selling up, marrying local mining manager Frank Burridge and continuing her mining hostelry on the copper field of Captains Flat, New South Wales.17

A tomb with a view

Years of moldering in his unmarked grave in the early Zeehan Cemetery may have prompted Thomas Goldie to ponder his situation. Why was he buried in a swamp? You couldn’t see squat. Why didn’t he get an eternal eyrie like the great majority at Linda, Weldborough and Balfour? The Linda Cemetery was like the moor in Wuthering Heights. Biblical tempests roared down it, smashing white picket fences, firing Huon pine headstones, scouring out inscriptions and matting the path with scrub. It would have been just like home on Mount Read.

When Tasmanian artist Raymond Arnold painted his series on the Linda Cemetery he borrowed Marie Pitt’s ‘thresh of the spiteful hail’ to describe the grave of 26-year-old miner Timothy Kaye, which since 1935 had been decimated by the elements.18 Pitt lived in a pine hut on what she knew as Mount Hamilton while her miner husband William Pitt developed pulmonary tuberculosis underground at the Hercules.19 Her poem ‘A West Coast silhouette (Tasmania)’ mixed the ‘spears of sleet’ with the ‘beat of hoofs, on the corded track’ as the pack team toiled up from ‘the Lead’ and the ‘clang of steel, at the change of shifts’ at Four Level.

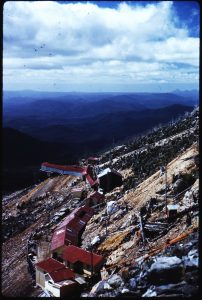

Today the world beneath the Mount Read Hotel site still stretches away to where distant Mount Heemskirk merges with the sea. Graffiti and a love token cut into the rock, broken crucibles, melted bottle glass, bricks and rusted iron all mark a spot within a cooee of the old Mount Read open cut and adit. No clang is heard from the bar-room piano. The Hercules is silent. ‘Half my heart is buried there’, Pitt wrote, ‘buried high on Hamilton, Lonely is the sepulchre with never stone for sign’.20 Thomas Goldie might have preferred this graveyard, with the moaning wind for an elegy and at least the scoured rock for a headstone.

- Nic Haygarth copyright 2021

1 Marie EJ Pitt, ‘A West Coast silhouette (Tasmania)’, in Selected poems, Lothian, Melbourne and Sydney, 1944. ‘Hamilton’ refers to Mount Hamilton, the modern-day name for the northern end of Mount Read.

2 Steve Spurling (Stephen Spurling III), ‘Towns on Tasmania’s west coast had a “wild west atmosphere”’, Examiner, 15 October 1955.

3 ‘Cricket club at Mount Reid [sic]’, Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 11 November 1896, p.2.

4 Eliza Reid Goldie was born 11 March 1893 to Thomas Goldie and Sarah McGrogan, birth record no.2662/1893, registered at Strahan, RGD33/1/76 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/detailnonmodal/ent:$002f$002fNAME_INDEXES$002f0$002fNAME_INDEXES:1052538/one?qu=NI_NAME%3D%22Mcgrogan%2C+Sarah%22, accessed 12 November 2021.

5 Warwick Frost, An environmental history of Australian rainforests until 1939: fire, rain, settlers and conservation, Routledge, New York, 2021, p.22.

6 Warwick Frost and Sarah Harvey, ‘Forest industries or dairy pastures? Ferdinand von Mueller and the 1885–1893 Royal Commission on vegetable products’, Historical Records of Australian Science, vol.11, no.3, 1997, pp.435–36; Warwick Frost, An environmental history of Australian rainforests until 1939, pp.163 and 174.

7 ‘The murder of Ah Gay Ong’, em>Argus (Melbourne), 19 October 1889, p.12; Deaths’, Leader (Melbourne), 23 August 1890, p.43. Marriage registration no.7220/1886 (New South Wales). The birth of Sarah McGrogan was registered at Goulburn, New South Wales, to William and Eliza McGrogan in 1857, birth record no.6909/1857.

8 ‘Strahan’, Mercury, 23 December 1893, p.1.

9 ‘The fire at Dundas’, Mercury, 9 February 1895, p.2.

10 ‘The Hercules GM case’, Daily Telegraph, 6 December 1895, p.3. See also Joseph Will, ‘Mount Reid [sic] discoveries—Stewart and Hart’s Section’, Daily Telegraph, 19 January 1895, p.8.

11 ‘The Hercules GM case’, Daily Telegraph, 7 December 1895, p.5.

12 Tender advert for Hercules Gold and Silver Mining Company, Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 5 June 1895, p.2.

13 For Goldie’s death, see Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 20 and 21 April 1896, p.2. The coroner attributed his death to chronic kidney disease (see inquest, 20 April 1896, SC195/1/71/10644, TAHO, https://stors.tas.gov.au/SC195-1-71-10644, accessed 11 November 2021). For other claims as discoverer of the Hercules lode, see, for example, James Griffin, ‘Mount Reid [sic] discoveries’, Launceston Examiner, 16 January 1895, p.3; Thomas Bateman, ‘Mount Reid [sic] discoveries’, Launceston Examiner, 17 January 1895, p.3 and 1 February 1895, p.3; ‘Mr HE Evendon’, Tasmanian Mail, 6 November 1909, p.18 and ‘Hercules Mine: discoverer to make claim in court’, Advocate, 19 December 1928, p.4.

14 ‘The late Mr Goldie’, Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 21 April 1896, p.3.

15 Geoffrey Blainey, The peaks of Lyell, 3rd edition, Melbourne University Press, 1967 (originally published 1954), p.247.

16 See Sarah Goldie’s dedications to her husband on the anniversary of his death: Sarah Goldie, ‘In memoriam’, Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 17 April 1897, p.2 and 18 April 1898, p.2.

17 Sarah Goldie married William Francis Burridge on 1 June 1898, marriage record no.571/1898, registered at Launceston, RGD37/1/60 (TAHO), https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/names/search/results?qu=sarah&qu=goldie, accessed 12 November 2021. See also ‘Queanbeyan’, Goulburn Post (New South Wales), 24 June 1902, p.3.

18 ‘Deaths’, Advocate, 27 February 1935, p.2.

19 It (‘phthisis’) killed him in 1912. See editorial, Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 3 April 1912, p.2.

20 Marie EJ Pitt, ‘Hamilton’, Selected poems.

A good read thanks Nic, spent a lot of time up there babysitting an excavator during rehab work around 1995 so had a good look around the area. Talked to an old chap that worked up there in the 1930’s the tales tales that he told me I will never forget. I also had the privilege of taking him back up there for a look with the company blessing at the time.

Having worked in Rosebery in early 60’s and explored many mines in the area as a mineral collector, nice to read a bit of history of the place.

I remember looking back at the view of Mt Read from below Godkin Ridge in those days. Sadly now no longer visible.