In 1891, three separate surveys were cut through the mountainous centre of Tasmania towards Zeehan. Engineers, local guides, axemen and packers worked to find a route for a railway from Ouse, Mole Creek or Waratah. It was part of a series of crazy parochial conflicts later called the ‘railway wars’.1

This blog is about our search for a camp used by a survey gang on the Mole Creek to Zeehan survey.

The Clue

I found the survey field books in 2009 but it wasn’t until 2015 that I gave them some attention. In one field book, the engineer in charge of the permanent work, WH Scott, recorded the location of one of his camps.2 He took compass bearings of surrounding mountains from a high vantage point nearby.

Mapping the Camp Location

I put Scott’s compass bearings onto a map. They focussed on a small area near a tributary to Wurragarra Creek and near the Lees Paddocks/Reedy Lake/Venetian Blind Track.4 However, it seemed an odd place for a camp. It wasn’t on the survey but about 1½ kilometres south of it.

The Pack Track

It turned out that despite being cleared and marked, the survey line wasn’t used for access. A completely different route, part existing track and part new track, was used to pack supplies.5 About 50 kilometres of pack track was cut.6 It was sketched on one of the survey maps and confirms Scott’s location of the camp site.

The pack track crossed Wurragarra Creek just above where it splits into channels on the flat at Lees Paddocks on its way to the Mersey River. The track then turned towards the survey. There is a mark, probably the camp, and a dotted line that is likely the creek that runs from Reedy Lake to Wurragarra Creek.

What Do We Expect to Find?

Huts were built for the survey in various locations. One was near where New Pelion Hut now stands, see our previous blog here.7 But this camp would have been a group of tents.8 There may have been little to find, little or no earth-works and maybe just some stumps of the trees that had been felled for warmth and cooking. However, 130 years of fire and decay may have destroyed them.

First Visit – 2015

Ian and I walked to Lees Paddocks and then followed the track as it climbed steeply towards Reedy Lake. It levelled out a little as we followed the southern side of a creek.

Finally, we reached a point on the track near the predicted location. If we could find the point where the engineer took his bearings then we would be confident that we were in the right area and then try to find the camp.

We started uphill through thick scrub. Within about 10 metres we found a few stumps. They were very weather worn but clearly cut stumps. We continued higher. Finally, we reached the top of the ridge. The location made sense but there was no evidence. The scrub was too thick to find the small low mound that would have been formed as a level base for Scott’s surveyor’s theodolite. Tall forest at every angle obscured the mountains that he had once sighted.

We walked back downhill to the track and left. The stumps near the track and the topography supported the idea that the camp had been in the immediate area. That was enough for me. However, Ian had only just started.

He asked Richard Sands, our history obsessed surveyor friend, to use his skills. He generated more accurate estimates of locations of the sighting point and the camp.

Second Visit – 2023

In March 2023, we were back with the team; Tim, Nic, Ian, Eddie and Jenny. Again, we planned to find the sighting point at the top of the ridge and then go downhill to the camp.

We had great weather and enjoyed the journey. This time we came from the west past Lake Ayr, McCoy’s old hut site and Reedy Lake. We crossed to the southern side of a little creek. It was familiar territory. The GPS told us where to stop. The sighting point would be uphill and the camp downhill. We sheltered briefly in the shade of a tree on the side of the track. Around us were a few old stumps that we hadn’t noticed in 2015.

We split in two groups. Four of us pushed our way uphill and two went downhill. The highest point on the ridge was about 5 metres from Richard’s predicted location. It didn’t take long for Eddie to find an unusual looking rubbly area of loose earth and stone. A closer look showed that the stones were small, of a uniform size and loosely packed. This was Scott’s sighting point. He needed a stable platform for the theodolite as he would have had to walk around it to read a full circle of landmarks.9 We now set our compass and headed back downhill to where the camp should have been. We crossed the track and into the scrub on the other side to go the exact distance we needed to travel. We couldn’t find anything.

As we often do, we regrouped and considered our situation. Tim and Nic had found an old bottle near the stream more or less below where we were. The waterfall marked in Scott’s field book had been located downstream. The camp had to be nearby.

We looked again. Again, it was Eddie who found it. Not much to start with, just a very small pile of rocks, but they were arranged like a chimney. And there was also the faintest suggestion that a levelled bench had been cut across the steep slope. Although it had almost disappeared under soil washed downhill. We had found the camp.

Benching is where a level step is cut into a slope, as shown in the picture below of a bench for a road. The earth in the uphill section – red is used to build up more of the bench downhill – green.

Chimney butt (P Brown Photo 2023)

There was the hint on the slope that the bench continued further to the east. It was about 17 metres long.10 After a little discussion we could picture the arrangement of the camp. A long bench had been cut into the side of the hill and the tents pitched in a line. The western most tent appeared to be the only one with a chimney. The others were most likely accommodation.

Final proof was a small odd shaped lump of rusty iron. Whatever it was. We photographed it. All in all, we were very happy with the day. We’d found the old camp and it fitted with the field notes from 130 years ago.

The lump of iron

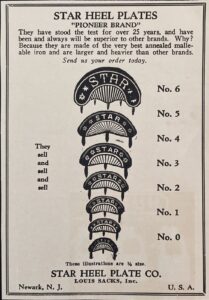

There were a few loose ends to tie up. Ian and Richard worked out that the rusting lump of iron was a heel plate for a boot. They are nailed into the heels to reduce wear. The crescent shape and the remnants of the nails helped identify it.

More about the camp site

Next was a trip to Tasmanian Archives in Hobart. A file on the railway survey contained letters from WH Scott where he described his camps. He stated that there were 5 tents, each about 4 x 3 metres. Scott had one tent as his office and ‘mess for self, assistant and foreman’. His assistant, Fred Hiller, had a tent which he shared with the foreman and one of the men. Six workers lived in two tents. The fifth tent was occupied by the cook and his stores.11

The documents also indicated that the camp site we had found was occupied in August 1891.

One last historical artefact needed attention. A few years ago, the late Simon Cubit had given us a photo that he said was taken of a camp on the railway survey. The men in it weren’t named and the location wasn’t known. Could we learn anything further about the camp site or the people?

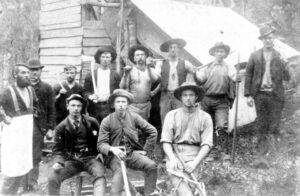

It took a lot of staring and chatting but we can say a few things about the photo. First it is WH Scott’s permanent work gang, rather than the flying survey gang under the Engineer in Charge or a second permanent work gang.12 From the topography, and the estimated time of the photo, April or May 1891, the location was at the Fisher River, not the site that we had found.13

The photo shows only one tent. It was the cook’s domain which was made of a fly with a roughly constructed chimney. It was probably a similar arrangement to the cook’s site that we found.

The carefully posed photo shows everyone with a tool of their trade. The tools and the clothing help identify each of the men.

In the front row, at the left-hand end, is the cook in his apron. He had no need of a broad-rimmed hat to keep off the sun and the rain. He was employed by engineer WH Scott to ‘make good bread, be clean and active’.14

WH Scott sits, probably holding a surveying instrument of some kind. He is dressed in a waist-coat, tie and jacket with a watch chain and a handkerchief in his top pocket.

Next is his assistant Fred Hiller.15 He started as a foreman but agitated for more status and pay. He also wears a waist coat, jacket and watch chain. He holds a shovel which had one use on the survey, to make the small level spots needed to site Scott’s theodolite. He probably built the siting point above the camp that we had found.

At the right-hand end, a carpenter holds an auger and axe. He would have prepared the numerous neatly squared and formed pegs and carved identifying numbers into the face trees at significant locations. The auger was used to form holes for elaborate reference pegs.16

In the back row, at the left-hand end is the overseer. He has no tools other than the force of his personality. The other men hold the axes that cleared the timber and scrub to a width of between 2 to 3 metres along the survey to allow Scott to take bearings. These six men quit work in May 1891 after some bad weather and a disagreement with Scott.17

An ending

In October 1891, the survey was abandoned without being completed. The Launceston Examiner remarked that

the parting of Mr Scott and Mr Hillier (sic) with the men employed on the work was of a genial character, the men being profuse in their acknowledgments of the kindness of both gentlemen, and much regretting to part with such able and gentlemanly employers – a strong contrast.

The cryptic ending ‘a strong contrast’ was not explained.18 A contrast to what? Was it the previous permanent work gang who had quit? Or the packers who stopped work and forced the flying survey gang to retreat after they ran out of food? Or was it the extended break at Christmas 1890 when the men preferred to work on harvesting on the farms rather than on the survey? Tension had run deep in the camps of the railway survey. Including between the engineers.

None of the railways was built. Another round of the railway wars returned in the late 1890s. This time a line was made, the Emu Bay railway from Burnie.

There is a much greater legacy from the survey. Our modern maps are labelled with the names that the engineers had given to some of the mountains and creeks. It was said that the survey had opened the Pelion Plains for the first time. However, this ignored thousands of years of Aboriginal history in the area. Today, when you follow the Arm River Track past Lake Ayr or the Overland Track from the Pelion huts to the Forth River you are on the survey line and in the footsteps of the engineers, bushmen, cooks, sawyers and packers who re-opened this country in 1891.

Copyright Peter Brown 2023

1 Geoffrey Blainey, The Peaks of Lyell, 6th ed. (Hobart: St. David’s Park Publishing, 2000). Tim jetson has used a broader term, route wars, which includes competition for tracks to new mining fields, Tim Jetson, It’s a Different Country Down There; A History of Droving in Western Tasmania. Circular Head Bicentenary Project Team, 2004.

2 The engineers performed two surveys. The flying survey quickly established the route for a railway. A gang followed performing the permanent work that cleared the route, extensively marked it and laid out the curves.

3 Archives Tasmania, Mole Creek to Mt Zeehan Parliamentary Survey Field Book No.2 PWD 231/187 WH Scott 1891.

4 This track is called Lees Paddocks Track on the maps but that confuses it with the track to Lees Paddocks from the Mersey Forest Road. It is also called Reedy Lake Track, probably because it passes that lake. It is also known as the Venetian Blind Track because it was marked by pieces of venetian blind.

5 In 2016, Simon Cubit wrote that, “it seems plausible that a pack track was cut up through the forest to Reedy Lake (from Lees Paddocks) to supply the survey effort’. Simon Cubit archives website https://webarchive.nla.gov.au/awa/20170112141501/http://pandora.nla.gov.au/pan/159505/20170113-0000/www.simoncubit.com.au/Pelion-tracks.html

6 Engineer in Chief of the survey Allan Stewart reported that the made 149 miles of preliminary explorations, formed 31 miles of pack track, blazed 47 miles of traverses, made 83 miles of trial surveys and prepared 56 plans, amongst other work.

Stewart described the permanent work as ‘laying out the tangent lines and curves from the large contour plan prepared from the traverse lines and cross sections. Pegs have been put in at every 10 chains (200 metres), also a peg and three pilot pegs at each tangent point, a large peg, 4in. by 4in., at each intersection, and a 2in. by 2in. peg at each secant. The numbers of the intersections are either cut in the pegs or on trees facing the intersection pegs. The centre line has been cleared of all scrub and trees for a width of from 6 to 8 feet. Trees and saplings have been blazed on both sides of the line so as to be distinctly visible one from the other. Substantial benchmarks have been left at every half-mile all along the line, and a list of these, with the heights and location, has been prepared.’ Allan Stewart, “Mole Creek and Zeehan Railway, report of the Surveyor in Charge’, Journals and printed papers of the Parliament of Tasmania (JPPP) No. 140 (1891)

7 Allan Stewart, JPPP reference as above.

8 Stewart tells us that in his report and the field book that in which the recorded location was marked with Scott’s name.

9 Expert advice from Richard.

10 Thanks for Paula McCulloch for taking this measurement.

11 24 Feb 1891 WH Scott to Engineer in Chief (Fincham), Tasmanian Archives, General Correspondence and Associated Papers Relating to the Construction, Maintenance and Operations of Specific Railway Lines, Mole Creek-Zeehan line, PWD214/1/145

12 A second permanent work gang under Oswald Roehricht that surveyed 7 ½ miles was made up of 4 men (Allan Stewart to Engineer in Chief, 26 Mar 1891). The flying survey was conducted by Engineer in Charge, Allan Stewart with camps set well apart but with rougher ‘flying camps’ between. 50 year old Stewart was experienced in railway surveys in England and Ceylon. Initially he worked with four men (Stewart to Engineer in Chief, 30 Nov 1890) but later full strength of the flying survey gang included 10 men (Stewart to Engineer in Chief, 21 Feb 1891). All references in PWD214/1/145 as above.

13 Stewart was near Lees Paddocks at this time and mentioned that he would have a photograph taken there ‘in due time’. He abandoned his work at the Mole Creek end of the survey at the end of April 1891 and moved to the Zeehan end, PWD214/1/145 as above.

14 Launceston Examiner, 6 Jan 1891.

15 Also spelt Hillier in some correspondence.

16 Scott’s field book describes the reference pegs as ‘4” square about 6 inches out of the ground with a ¾”hole in centre of each. Instead of trenches logs 5 ft long have been placed in the direction of the line, secured by four stakes driven into the ground. A …… pole has been left at each reference peg.’ Field Book No.2 PWD 231/187 WH Scott 1891.

17 Scott to Engineer in Chief, 9 May 1891, PWD214/1/145 as above

18 Launceston Examiner, 23 Oct 1891.

A great story and well written. Thanks again for sharing. I always love how you guys can put a story together with such small bits and pieces. Well done

Thanks so much Paula. Great praise coming from the best hut hunter around. Love your facebook huts page

As a point of interest I was told by Simon Cubit that there were some rail survey huts near Survey Creek downstream from Lees Paddocks. The survey line went up below the cliffs of Pillinger to arrive finally at Pelion Plain. I found a line of old cut off stumps near the plane wreck which may be the survey line. I haven’t followed the line very far yet but I may have another look around there.

Thanks Rod, we’d heard about those huts but haven’t had any luck finding them. Even remember the location being pointed out on the side of the Lees Paddocks track. We should work on this together.

That is the survey near the plane wreck. Remarkably well preserved. But now we understand that there may be survey marks as well as the cleared route. Better go back again.