It seems like we’ve known about Gads Hill forever. But it was just a place to drive past on the way to more interesting spots. It never captured our imaginations enough to be a destination.

For Ian Gads Hill goes back more than 50 years to when he listened to his father and mates tell many a yarn. Some mentioned this remote highland stock station. Simon Cubit and Nic Haygarth have told us its stories too.[1] They were about the men and women who lived in this isolated spot and the people who passed through.

Simon and Nic’s stories were well researched and well told but something was missing. It has taken a while to work out what that was – a really strong sense of place. This wasn’t helped by a complete absence of photos of the people and of the homes. We needed to bring the place to life. This started when Ian decided to bring the team’s focus on Gads Hill.

What is Gads Hill?

Gads Hill is between Liena, on the Mersey River and Lorinna, on the Forth River. From the river flats at Liena it is a formidable hill and a very steep to climb. But once you are on top of the broad high plateau between the Mersey and Forth Gads Hill is just a small bump among the plains. Its grassy plains were an important stop-over for livestock in the early days of the, at the time, struggling Van Diemen’s Land Company (VDL Co) and the much more successful Field dynasty. The VDL track was an important link between the remote grazing lands and the markets in the towns of northern Tasmania. At Gads Hill it was joined by a track from pastures to the south at Howells, February and Pelion Plains.

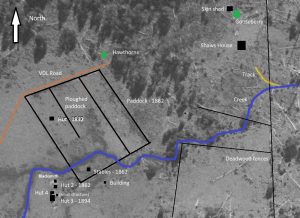

William Field junior built a hut on a plain near Gads Hill in 1842 and it gave its name to the stock station. Later it was called Old Station when a new camp was built further down the hill in the 1920s. Around 1900 Mark Shaw, a Field stockman, built a three bedroom timber house on land to the east of Old Station. Nic has told us the stories of these people in earlier blogs.[2]

The first searches and mistaken identity

About five years ago, a surveyor friend sent Ian a map with a hut marked on it. He knew that Ian loves hunting for highland huts. Ian tucked it away ready for the day when it would be useful.

In 2017 Gads Hill finally became a destination. Ian took out the map that led us along a forestry road. We parked on the edge of a grassy plain and followed a creek to a small elevated paddock surrounded by a single strand of barbed wire.[3] Here and there piles of stones peeped out of grass tussocks. We found more rocks by probing the grass with our boots (the area was far too snake friendly to use our hands). We couldn’t see enough to make sense of it but they appeared to be the ruins of chimneys. It was a great location for huts – on a natural rise beside a creek and relatively protected from the elements like fire, storm and flood. We decided that we had located the Shaws’ homestead. Which meant that the Fields’ Old Station was further west. We were wrong but it was early days and we were learning.

To be honest we were underwhelmed. It was one of the easiest hunts we’d had. 15 minutes across an open paddock and straight onto a site that was already known. We didn’t go back for a couple of years, Gads Hill still hadn’t captured our imagination completely.

Our return in early 2019 didn’t start well. We searched to the west of the chimneys for Fields’ huts and didn’t find a thing. Not surprising considering that it had been abandoned for about 60 years. Whatever was there may have burnt down, been removed or just decayed and then whatever remained would be hidden under the big tussocks of grass.

It was time to get a little more serious. We dug out old surveys and maps and looked for clues. Then we argued back and forth about what they meant. Soon it was obvious that we had made a fundamental mistake. The chimneys were Fields’ not Shaws’ and we needed to look east, not west for Shaws’ home.

Ian headed back out, parked the car near where we had been before, got out and almost straight onto Shaws’ house (it does help if you know where to look). Not that there was much left. A forestry road ran straight through it. There was a pile of soil and broken iron artefacts pushed up beside the road. For the first time we understood the general layout of Fields’ and Shaws’ holdings.

The unsuccessful hunt for the first hut but …

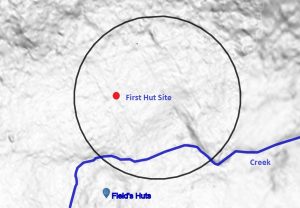

Fields’ first hut burnt down about 1847. It was marked on an old survey as being out on the plain to the north east of the Fields’ later huts and inside a paddock made by post and rail fences. It wasn’t a great spot. It may have been beside the VDL track but it was not convenient to the creek, on poorly drained ground and unprotected from fire and the winter westerly blasts.

Ian looked for the first hut and other features shown on the old survey. He found plenty. A large pile of stones (enough for a large chimney), hawthorn trees and bits of a fence line. He was filling in some details.

I joined Ian on his next trip. We looked around the rocks. There was nothing else to confirm that a hut had been there. Now we got technical with a long tape measure, compass and some bright yellow tent pegs. We walked the whole area and put in a peg every time we found a rock. They were spread over about 90 metres. A little more work and it was clear that there were two rows, each in a straight line. The chimney had turned into something else. Possibly the marked route of the VDL track which ran along the top edge of a paddock. They were in the right place but they stopped suddenly at the western end of paddock. We soon had another theory.

Our new idea was that the rocks were the chimney of the old hut but they had been cleared from the paddock to allow it to be ploughed. They would have been thrown up against the nearest fence line. This meant there was a glimmer of hope for finding the first hut. We crissed and crossed that area, and looked under every blade of grass. Not a stone, not a depression, not a post hole, nothing. We gave up on the first hut, for the moment.

A good look around revealed some long ruts. Splinters of timber on the ground were scattered along the ruts. These were the fence lines of an old paddock. The ruts had formed when cattle milled along fences and the timber was the old post and rail fences.

The final act in the search for the first hut came when we noticed that the outline of the paddock we found matched the old 1862 survey precisely. That gave us a reference and we now knew the location of the hut site within a few metres. And this location was only lightly grassed making any feature there easy to see. And we didn’t find a thing. Then we finally worked out why.

The paddock had been so heavily ploughed that the hut had been erased. Everything to do with it had been destroyed or removed. The long furrows are still visible on aerial radar mapping.

We could not find the first hut but during the chase we had located the paddock from the same period and the line of the VDL road.

We’re not going back there again

We needed one last detailed search before we called it a day at Gads Hill. Nic joined us on this trip to view the evidence and for us to discuss our interpretation of the landscape. One of the great things about our small team is that our different backgrounds and life experiences compliment each others’.

We stepped out of the car near the debris of Shaws’ house. We showed Nic a gooseberry bush in just the right location for Shaws’ garden, on the northern side of their large house. A nearby neat row of stones on the ground was probably the foundations for a small hut in the garden shown in the 1950 aerial photograph. We looked over the VDL track, the paddock, the probable location of the first hut and skirted around the Fields’ later, overgrown, hut site. We left after a full morning knowing that we couldn’t do more. As we drove off we were certain that ‘we won’t being going back there again’.

Over a leisurely lunch we chewed our food and our ideas about Gads Hill. Then we realised that we had forgotten a stable that was also on the old 1862 survey. The location was in the south western corner of the paddock, near the later huts, and the creek. We went straight back over. The subtle shadow of the stables was exactly where it was supposed to be. Now we were finished. We’d found many artefacts. Fields’ buildings were beyond understanding, either destroyed or under a thick layer of tussocks.

Nic’s research also helped bring the site to life. He turned up an interview with Ethel Shaw, who had grown up at Gads Hill in the early part of the 20th century. Her words threw new light onto the site. She spoke about day to day life and brought out the details that often don’t make it into written histories. Her recollections of events big and small breathed life into cold history. She remembered the farm as a place full of people; her family’s daily rituals, the coming and going of stockmen, the dances, the sudden passing of her mother in the family garden. And she listed, for the first time, the many buildings at Gads Hill. Many more than any other source.

We won’t be going back there again, again …

Luckily Ian couldn’t keep away. He found that the grass at Fields’ hut sites was a lot thinner. Time for another look. We could see more of the rock piles and even the rocks that held the bearers for the floors of the huts. It took all day to survey the rocks, bumps and scars on the ground left by the huts; chimneys, foundations and garden beds. All the time we kept a close eye on two very healthy tiger snakes sunning themselves on a big chimney butt. We could start to make sense of the layout of the huts and combined with the surveys we could decide, roughly, when each of them stood.

We were stunned to identify three huts, a blacksmith’s, two gardens and a small square shed. We could see the sequence of huts and buildings.

The first hut out on the plain didn’t last long, 1832 till 1847. By 1862 the next hut was built on the raised ground near the creek. It was only 3 by 4.5 metres with an entry beside the fire at the south-east corner of the hut. It survived past an 1894 survey and was gone by the 1950s.

The third hut was built before 1894 and was the last standing in the 1950s when it was captured by an aerial photograph. It was substantial, at least 8 by 5 metres with a massive chimney. And possibly a two metre porch on the southern side overlooking a garden ringed by stones.

The fourth hut was just to the north of the third. It came and went between surveys. It was so close and on the same alignment as the third and probably built after 1894 and burnt down before the aerial photo in 1950. It was about 5 metres square with a 2.5 metre extension almost linking it to the third hut. This was probably accommodation for the visiting stockmen.

The other features were a blacksmith’s on the northern edge of the raised land, the stables near the creek that was captured in the 1862 survey, a small one metre square building near the third and fourth huts and an unknown structure a little south of the stables.

Imagining the Old Station

Now we weave the stories of the people who lived and worked on these high remote plains around the landscape that they lived in. We can stand where their homes once were and look across the plain and imagine the buildings, fences and cattle that once filled the place.

The artefacts that we found are links to past events. The gooseberry bush in the Shaws’ garden where Bertha died in 1926. The hawthorn trees recall sturdy hedges that may have lined the edge of the plain. The tiger snakes resting on the stone chimney of the big house reminded us, all too much, of Harry Stanley’s famous snake stories.

We can stand in the middle of the big house (the most southern), in front of the massive ruins of the chimney. We can see what we have been told, that it was big enough for some of the six Bonney children—’Arthur, Albert, Lindsay, Millie, Dolly and Lena—to sit virtually inside’.[4]

With the huts and homes coming to life it is easy to think back to a time when the post and rail fences still crossed the plain. When the cattle and milk cows would have made their gentle sounds as the shadows lengthened and the last of the long afternoon sun lit the grass and trees in gold.

We can imagine how this solitude would have changed when the visiting stockmen drove in their wild back country cattle. They would have made a noise in the unfamiliar confinement of the paddock. Arthur Collins, Dick, Frank and Humphrey Brown would have moved into their quarters next to the house. It was time to swap stories, catch up on family events and yarn. It was also time to celebrate friendships with a bush party.

Listen in the quiet and you might almost hear the sound of ‘Mark Shaw wresting a tune from the squeezebox’ accompanied by calls and shouts and the sound of heavy boots as the Bonneys practised the step dance.[5] Out would have come the food, the booze, harmonica and the children to dance and yarn the night away.

For us Gads Hill is not a field of grass and myths but a place where history lives on.

[1] Simon Cubit, Mountain Stories, Echoes form the Tasmanian high country, Vol. 1, Forty South Publishing, 2016, p 12-15. Nic Haygarth, A view to Cradle, 1998, p 33, 68, 131.

[2] https://mountainstories.net.au/blog/old-station-gads-hill-no-3-the-bonneys-and-the-shaws/

https://mountainstories.net.au/blog/old-station-no-2-harry-and-mary-stanley-a-gads-hill-double-act/

https://mountainstories.net.au/blog/old-station-gads-hill-no-1-field-brothers-highland-base/

[3] Later we found out that the wire fence was put up to protect the site after discussions between Simon Cubit and Forestry Tasmania. They knew that it was the Fields’ site. The Shaw’s house wasn’t so lucky.

[4] https://mountainstories.net.au/blog/old-station-gads-hill-no-3-the-bonneys-and-the-shaws/

[5] Also see Bonney and Shaw blog

Would any of the rocks be markers of the Innes track? My understanding is the track was to run through the property but followed the western boundry so as not to disturb fencing exactly.

Good point David. The Mole Creek Track (aka Innes) did run through the property near the western side.(Here it roughly followed the much older track to Howells Plains). The alignment of rocks we found ran east-west and aligned very well with the survey marking the VDL track. The Mole Creek Track would run north-south and was a little further away.

Why did he call it Gad’s Hill? The most famous Gad’s Hill is the house where Charles Dickens lived at No, 6 Gad’s Hill Place, Higham Kent. Dickens’ neighbour at Gad’s Hill, Cpt Edward Goldsmith was interested in the VDL Company, and acquired land in the area in 1841 while in VDL. Another Gad’s Hill appears in The Great Gatsby, interpreted as God’s Hill by some critics. The Gad’s Hill, Missouri Train Robbery took place on January 31, 1874, etc etc etc

A good question. But without knowing who exactly named it, we don’t know why it was named.

The name seems to post-date Hellyer or Fossey of the VDL Co, whose reports and early maps only refer to it as Emu Plains. So it wasn’t applied in the time of the cutting of the VDL Co Track. The name was in use by 1841, when Strzelecki mentioned it. Ford didn’t know the term when he made his trip on the VDL Co Track in 1842, but it appeared on Kentish’s map of his new road c1844.

Edward Goldsmith was the captain of the barque Wave, trading between Hobart and London. The land that he acquired was 100 acres in the County of Lincoln, Parish of Sharland, in 1840. He sold it by 1841 to George Bilton. The Parish of Sharland later became the Parish of Gainsborough, and Goldsmith’s land was near the Nive River on the Central Plateau, a long way from Gads Hill. Is there any evidence that Goldsmith ever set foot on Gads Hill?

It is unlikely to be connected with Dickens as he didn’t buy this property until 1856. Gads Hill also occurs in Shakespeare’s Henry IV as Gadshill, both a place and a highway robber.

Just to add a little further confusion, Gadd is a family name that is known in the region. Gad has been misspelt this way on at least one offical sign in the area (Gads Falls if I remember correctly).

Hopefully you might have more luck with finding the origin of the name than we have.

Fascinating research. So interesting to be able to reconstruct a site and the lives lived there from your investigations. Are you all amateurs or have you trained in some area of expertise? (apologies if I should know this) I have found the site of an old farm on the east coast that is very overgrown. There were obviously extensive fences and buildings and I have a few local stories but actually putting it all together, knowing where to research and surveying the site are extremely difficult. Any hints on where to start

Hi Nola,

Thanks so much for your comments. We are amateurs and professionals. But the most important thing is to be tenuous. Expect to chase the subject for years until a plausible result is reached, our current team often has multiple subjects simmering for long periods until something re kindles the flame and helps produce a desired result. You’ll probably spend 10 hours researching for every hour visiting our site. But that time helps you get a picture of the people and when different features were built etc.

The three main areas to look at are the written record (archival documents, surveys, newspapers) oral histories (often in local history books) and the landscape.

County charts are useful. You can find them either on line (The List) or at the library. You can establish who it was granted to, then can do a title search through The List database – or just put the name and acreage or block no into Trove (the online newspapers index). Surveys are available online (The List). Surveys sometimes show buildings or other features (but often not that accurate).

Newspapers are useful for the people involved and what happens to them on the property over the years (Trove). Search for local histories. Keep hunting for local knowledge which may lead to photos or the like. Old photos of your site are like gold. Tasmania archives have a lot of photos that can be searched online.

Make multiple visits to a chosen site – you will find something new each time you visit. Old aerial photos go back to about the 1950s and they can be very useful to see what the site was once like. If you know where to look it can save a lot of random wandering (not that isn’t useful either)

When you put all the facts together you get a much greater understanding of your site.

Good luck

Hi Peter,

You explorations, excavations and explanations are pretty accurate I reckon.

Gadd was part of the original surveying party I think (but not sure now). I still spell it as Gadds Hill and Old Gadds Hill Rd from Liena to the New Station, well to Oliver’s Rd now and Gadds track from Oliver’s Rd to the New Station.

There was an old single furrow plough left on a grassy plain to the east of Fields’ hut (was there in the 90s)

I never saw the gooseberry bush or the hawthorn(s) there.

To the north of the main house the VDL road passed through two big gate posts that no longer existed by the late 80s but the place was pointed out to me by Dick Miles when he was alive.

I could never find any trace of the VDL track from where Oliver’s Rd would have cut it, going to the Old Station, despite thorough searching in the bush. It would have been really steep!

The other name for the area around the old Station was The Park or the Old Park.

I’m interested to know how you arranged for aerial radar mapping of the site. This tool, bring non-intrusive, can reveal details that are otherwise hidden. Thanks

Hi Mark, the rader is a fantastic tool and even better because you can view it online for all of Tasmania. Look to The List, the Tasmanian government Land Information System at https://maps.thelist.tas.gov.au/listmap/app/list/map Then choose hillshade from the dropdown menu under Basemaps. Some areas have better definition than others.

Mark Shaw was my children’s great grandfather. as i read this article i shed a tear for all the stories my father-in-law (Roy Shaw) told me of his life growing up on the ‘Old Park” . i was just too young to recognise the significance of the HISTORY he was telling me.

i know their life was extremely hard but i suspect it was a happy, simple life. the harshness of that life was still very evident when i went to live in Liena nearly a lifetime ago.

Thanks so much for this series. I enjoyed a good look around the old site today, made much more sense after reading this carefully a couple of times.

Great work.