Another Barn Bluff Copper mystery

Eddie

I’ve been lucky enough to know Eddie Firth for years. He is a great walking companion; extremely experienced, easy to get along with and an infectious enthusiasm for the history of Tasmania’s high country. In many ways he is part of this history. Many would know him from his years as a ranger in the Cradle Mountain – Lake St Clair National Park.

A few years ago, Eddie directed me to an old piece of machinery – a rusty wheel and fittings on the dirt floor of a shed. It was interesting to see how it was constructed and how it would have worked. It was a small Pelton water wheel.

Pelton wheels were very popular with miners in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. They were perfect to power machinery in remote locations if there was a a good supply of water. Pelton wheels could drive many kinds of equipment; electrical generators, pumps, air compressors, crushers, stamper batteries, etc. They were small and relatively easy to transport. And they were much less complicated than alternatives like steam engines and very cheap to run. Importantly they could generate much more power than traditional water wheels because they used the pressure of water from a pipeline from an elevated source. These days huge Pelton wheels are used to produce hydroelectric power.

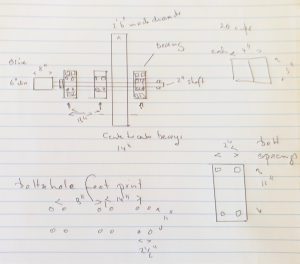

This Pelton wheel that sat in front of me had the distinctive features – the ring of split buckets and robust construction. The buckets were bolted on to make them easy to replace if worn or damaged. It had been held in place by three large bearing blocks. Two secured the wheel and the third stabilised the long shaft with a drive pulley at the end. The bolts that would have held it to a wooden frame hung uselessly from the bearing blocks. The small diameter drive pulley would have driven a broad flat belt that then powered machinery of some kind. Eddie had told me about its history.

The wheel was supposed to come from the Devon mine. It was one of many mines; small and large, successful and failures, in the country north of Cradle Mountain. For years the mine had clung to the side of a deep gorge cut by the Dove River. Although it was discovered in 1892 it didn’t really get going until 1899.2 It produced lead ore (galena) in fits and starts between 1902 and 1912. Many people dabbled with the mine since then but to little effect.3

An artefact without a home

But there was a problem with this story. Like so many objects in someone’s shed or a museum, it has been moved from its original location and this weakens its connection to its history. Do we really know that its story is right? If you are lucky you can talk to the person who retrieved from the bush. But often information is second hand and can get confused. Could we tie this wheel to the Devon mine?

But Eddie had an idea that would add to the history of the wheel. He suggested that it might have started life at another place. That mine was the inglorious failure that was the Barn Bluff Copper mine at Commonwealth Creek which was just a few kilometres south of Cradle Mountain.

Barn Bluff Copper mine

Eddie knew that I would take that bait. We have both been interested in the Barn Bluff mine for years. In an earlier blog we have told the story of T J Connolly’s disappearance on the way to this mine. (see here – link)

A good few years ago, I had stumbled along behind Eddie on a long and fast walk to Commonwealth Creek. We stayed in the nearby hut and he showed me around. There are a lot of things to like about the place.

The location is stunning. First follow the Overland Track south and turn east near Barn Bluff for a few hours of off-track walking. You stop just a little way from the edge of the Forth River gorge. The trip is worth it just for the scenery. The mountains of the Cradle Mountain – Lake St Clair area are all around. On clear evenings, the nearby rocky columns of Mount Oakleigh glow like gold (or like copper) in the evening sun. A little, well built, hut sits by an unnamed tarn surrounded by a button-grass meadow. It is sheltered from the more turbulent westerly weather. Built by the Hydroelectric Commission, it housed workers who gathered rainfall information for the planned Forth River dams.

Over 100 years ago there were was a nest of huts in the valley carved out by Commonwealth Creek in its short journey from Lake McRae to the Forth River. In the days before the Overland Track, well-worn tracks linked those huts to Tullah in the west and Mole Creek to the east. It was the location of the Barn Bluff copper mine. Its story has been told a few times, although its history hasn’t been captured fully yet. 4

Copper was discovered in the 1890s and after a brief and exciting life it was abandoned in 1904. The mine produced nothing more than a lot of breathless newspaper reports and holes in the pockets of its investors.

For me Commonwealth Creek is fascinating because the location is amazingly beautiful, the decayed artefacts that tell the story of mining are still discernible under thick layers of leaf litter and the crazy story of the development of the mine.

The mineral booms of the 19th and early 20th century were full of people who were enthusiastic about their mines and oversold their potential. They overstated how rich their mines were, how big, how inexpensive to mine and just how wonderful they were. Against this kind of speculative exaggeration, the Barn Bluff Copper, Gold and Silver Company set the benchmark for bullshite.

EC James promoted his mine with a lot of wild statements. Just one example of many is; ‘Bulk assays, developments, geologists’ reports, all prove Barn Bluff to be the biggest mine in the world’. A Queenstown newspaper devoted an editorial to James’ comments calling it ‘insensate drivel’.5 But more of that in a later blog.

The wheel’s history

Did the Pelton wheel come from the Devon Mine?

It is very likely that it was at the Devon mine. This is the story that comes with the wheel and it is supported by historical information. The mine was reported as having a Pelton wheel working in July 1904.6 It was reported as being 2 ½ feet (76 cm) diameter.7 The wheel in the shed is that size. Unfortunately, there were no manufacturers markings on the wheel so it couldn’t be linked back to the supplier or their records. That would be the gold-standard proof.

But what about the Barn Bluff Copper mine at Commonwealth Creek? Proving that link was going to be more difficult.

The two mines are within a few kilometres of each other. Any equipment being removed from the Commonwealth Creek mine would be prime pickings for the Devon mine. Taking it back down the Razorback (Barn Bluff) Track to the Forth River and up from Lorinna would be fairly easy.

The timing for that transfer is tight but plausible. By January 1904, Barn Bluff Copper had failed. It was ‘considered amongst the derelicts’ and it was said that it would never be mined again.8 There was talk of selling the mine. There would be a period of about six months for the wheel to move those few kilometres down the Forth River valley.

The newspapers of the day were silent on when the machinery was removed from Barn Bluff Copper and where it went to. There are no reports that say where the Devon mine’s wheel was sourced from. However, if the operators of the Barn Bluff Copper are to be believed then it cannot be the same wheel.

There are several reports that the Barn Bluff mine had ordering two 4-foot diameter wheels. Do we believe this? Given EC James’ record of overstating everything it is possible they did in fact have 2 ½ foot wheels. After all he, and his mine manager, exaggerated the grade of the ore, when the track to the mine would be open and even the lengths of the water race that supplied the Pelton wheel. Depending on the day it could be 1200, 400 or 230 metres long. He even claimed that Commonwealth Creek’s water supply rivalled Niagara Falls in the USA.9

Eddie had a simple and elegant way to resolve this, inspect the physical remains. In 2010, he had shown me the rotting bed logs that had held the machinery. Could we match the locations of the bolt-holes in the logs to the bolts on the Pelton wheel?

To be continued …

Copyright Peter Brown 2022

1 Backcountry Explorers Old Timer Tales – http://www.backcountryexplorers.com/story-blog

2 Jennings, IB, Geological Explanatory Survey report, One Mile Geological map series 55-645 Middlesex, Tasmanian Department of Mines, 1963, p 132, Nic Haygarth, A View to Cradle, 1998, p 82.

3 McDougall, J. EL14/2006 “Dove River” Annual Report 2008, Pluton Resources Ltd, November 2008, Mineral Resources Tasmania,

4 Simon Cubit, ‘Mountain Stories – Volume 2’, 40 South Publishing, 2017, p 197; Tim Jetson ‘Almost a Walker’s Paradise: A history of the Cradle Mt-Lake St Clair Scenic Reserve to May 1922’, PhD Thesis, University of Tasmania, October 2005; Tim Jetson, Journal of Australasian Mining History, Vol. 7, September 2009

p 39, ‘That some rich lode amongst these hills is waiting for us yet’; Nic Haygarth, ‘A View to Cradle’, 1998, p 81.

5 My Lyell Standard, 4 Mar 1901. James’ didn’t limit his wild promotions to mining see Nic Haygarth, Proceedings of the 19th Australasian Conference on Cave and Karst Management – Ulverstone, Tasmania, 2011, A cup of tea with your cave, madam?’: cave tourism as a cottage industry at Mole Creek, Tasmania 1894–28

Insensate – completely lacking sense or reason

6 Examiner, 7 Jul 1904.

7 Examiner, 9 Apr 1907.

8 Examiner, 26 Feb 1904, Mercury, 19 Jan 1904.

9 Mercury, 21 Oct 1901.