Ronald Smith (1881–1969) never prospected with his famous father, James ‘Philosopher’ Smith, but took to the Tasmanian highlands like they were in his DNA. During the years 1903–14 he made more than a dozen hikes into the Forth River high country. Some of the places he visited would have been lost to history if not for his documentation with pen and camera.

On a stiflingly hot day in 1907, 26-year-old Smith set out on bicycle from the family home, Westwood, at Claytons Rivulet near Forth, with nineteen-year-old Robin (Bob) Adams. It was a Boxing Day trip, and people were outside enjoying the post-Christmas break. Adams carried a gun, Smith a Stereo Hawkeye roll film camera, and both had several days’ provisions: for Smith that meant three loaves of bread, about two kg of tinned meat, some butter plus coffee and sugar. He would have used a billy to boil water over a fire. Leaving their bikes at Sprent, the pair shouldered their swags as far as Smiths Plain under Black Bluff, where they ensconced themselves in the Smith family’s 18-foot-by-ten one-roomed hut.1

Smiths Plain place took its name from being Philosopher Smith’s point of entry to the high country. Many times the hardy Forth prospector must have squelched his way through the low button grass and cushion plants on the brow of the Black Bluff Range, snow or sleet blurring out the towering landmarks of Cradle Mountain and Barn Bluff, on his way to the Lea, Dove and upper Forth Rivers where he made discoveries of gold, silver-lead, manganese and copper.2

The copper was on a small creek running into the Lea River. He made the discovery in 1862—a time when Tasmania’s mining legislation only made provision for the extraction of gold and coal.3 The Waste Lands Act No.4 (1867) corrected this, enabling Smith to secure a 100-acre prospecting claim on the Lea River ‘about half a mile from Rocky Creek [the Fall River] near the west end of Stormont’ in 1869.4 Edwin Cummings, one of the prospector’s collaborators of the time, is believed to have tried to open up the copper mine, but it was swallowed up in the excitement about the Penguin silver mine and the Mount Bischoff tin mine in the early 1870s.5

However, Philosopher Smith never forgot about his copper show. Even when mining had made him a gentleman, he continued to support Tasmanian mineral discovery by employing prospectors as farm hands, giving them a living through the winter. One of these was the unrelated Alf Smith, who built a hut at the Lea River copper show for the Lea River Prospecting Association (LPA) in the wake of the Mount Lyell copper boom of the late 1890s. In 1903, six years after Philosopher’s death, and more than four decades after indications of copper were first detected, Alf Smith was driving to cut the copper lode when, he suggested, ‘something good may be expected’.6

Nothing good turned up. The United Copper Crash of October 19077 wiped the shine off copper altogether for a time, and it possible that no further work was conducted, making this just one of the hundreds of dud mining shows dotted across the Tasmanian highlands.

For Smith and Adams the little mine was another staging post on a hike through the highlands. Alf Smith might have been filling his dreams with gold or snoozing off his holiday cheer back at Westwood while the hikers lay listening to rain belt the shingles of the Smiths Plains Hut. Undeterred by the dramatic overnight weather change, the two men made a determined push on next morning through steady rain. The track over the exposed eastern flank of Black Bluff led them to Alf Smith’s other hut, at the Devonport Gold Mine, where they arrived soaked to the skin. Finding the hut filled by a picnic party of three men and three women from Sprent, however, they continued on in their wet clothes, making for the LPA Hut. Their fingers were numbed with cold as they descended the range steeply to the original Tiger Plain, a low button-grass flat on the northern side of the Lea River where Philosopher Smith had encountered thylacines during his prospecting days.8 Golden Cliff Creek, draining a deep gorge, was running a banker, their only choice being to wade it, with the water reaching up to their coat tails. The Lea River was flooded, but their nerve held firm as they negotiated the crossing log to the southern side and, following a track, they reached the LPA Hut about 180 metres from the river at 1.40 pm.

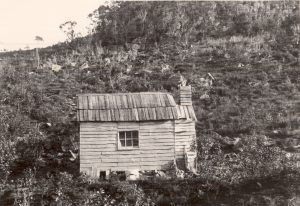

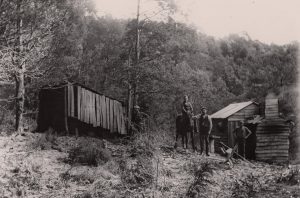

This was a tiny split timber hut measuring about eight feet by ten, lined with bags, with a fireplace at the eastern end beside the door and a wide, wooden, firebox chimney. A single sash window with six panes on the northern side provided light. Between the window and the fireplace was a fixed table, with a fixed bench beneath it and the fireplace. There was one pull-down seat attached to the wall and a double bunk, suggesting that the hut was designed for a single miner or two miners at most. A separate blacksmith’s shop was being used as a woodshed. Snow began falling at about 5 o’clock, and the two men settled in for the evening, relieved to be out of the elements. 9

The rain and snow abated long enough next day for Bob Adams to shoot two currawongs to supplement the larder.10 With the barometer dropping, suggesting no immediate improvement in the weather, Smith and Adams decided that, rather than attenuate their cabin fever, they should head home on their fourth day of their trip. Smith never returned to the LPA Hut. By 1909 the Cradle Mountain Road, which was gradually being improved south of Wilmot, had replaced the track over Black Bluff as his access route to the highlands. He cycled, rode and drove it for the next 60 years, with his Indian Standard motorcycle and particularly his 1920s Chevrolets becoming something of an institution on that road. Smith’s houses on his land at Crater Creek (1925–36) and Mount Kate (from 1947) employed the same bush carpentry as the huts he had frequented in his youth.

Rediscovering the site

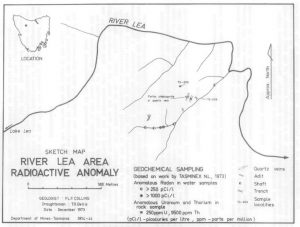

But what remained of the workings and the tidy little hut at Copper Creek? Was another of Philosopher Smith’s small stepping stones along the path of discovery abandoned and long forgotten? Given my interest in tracing Smith’s progress towards unearthing the world’s greatest tin mine at Mount Bischoff, in 1993 I wanted to track it down.11 I had four assets: the 1905 photos of the LPA Hut; an old Mines Department map with ‘old copper workings’ pencilled on it; a 1973 report on a radioactive anomaly at the copper workings;12 and David Duff, an incorrigible mine rediscoverer, for a companion.

David and I spent New Year’s Day 1993 plunging through thick scrub in the rain. Within two or three minutes of reaching Copper Creek we had located a 20-metre-long adit driven into the western bank. Other adits, trenches and shafts were easy to find—but where was the hut site? Ronald Smith had described it as being 200 yards (about 180 metres) from the Lea River but 100 feet (about 30 metres) above it in elevation. There was no guarantee the hut was at the mine site, and the steep, scrubby hills above the workings yielded no clues. The same went for a second trip to the site a few months later.

Happily there were no mutations as a result of visiting the ‘radioactive anomaly’, and I forgot all about Copper Creek until Paula McCulloch contacted me in 2017 about her several trips to the copper workings near the Lea River. In the meantime the bridge across the Fall River had been washed away and the logging tracks which gave easy access to Copper Creek had overgrown. Paula had a similar experience to David’s and mine, being impressed by the work of driving into solid rock but finding no axed tree stumps, chimney butt, hut platform or hut foundations.

The best thing Paula and I could do for this hut hunt was to introduce Ian Hayes’ forensic eye to it. Examining the hut photos, maps and Ronald Smith’s account of his 1907 journey, Ian quickly pinpointed where he expected the hut to be. Disappointingly, he was about 100 metres out. More disappointingly, the site of the hut at the top of the slope down to the Lea River was at the end of a 1960s logging operation and had been pummelled mercilessly. Logs, mounds of bulldozed earth and ferns obliterated the hut site. However, the site was discernible from the skyline and vegetation in the 1905 photos.

There were wattles but no eucalypts in the immediate vicinity of the hut—and so it remained today. All we had to show for the site was an old crosscut saw blade which Paula found protruding from the ground. Had this blade sawn timber across the trestle bench seen in the foreground of Smith’s 1905 hut photos? The answer lies buried in the ferns, along with the bottles, nails, china and other century-old shards of a working life in the Tasmanian highlands.

Nic Haygarth, Paula McCulloch and Ian Hayes

1 Ronald Smith diary, 26 December 1907, NS234/16/1/4 (TAHO).

2 For silver-lead on the Dove River, see JE Calder to James Smith, 19 February 1864, no.60B, NS234/3/1/1 (TAHO).

3 JE Calder to James Smith, 7 March 1862, NS234/3/1/1 (TAHO).

4 Document no.131, dated 24 November 1869, NS234/3/1/1 (TAHO).

5 ‘Mineral discoveries’, Examiner, 28 September 1908, p.2.

6 ‘Middlesex notes’, Examiner, 9 July 1903, p.2.

7 See, for example, Robert Sobel, Panic on Wall Street: a history of America’s financial disasters, Beard Books, New York, 1999.

8 James ‘Philosopher’ Smith believed that tigers congregated here to feed because the game was driven here by the Middlesex stockman’s dogs. See ‘JS’ (James Smith), ‘The Black Bluff’, Launceston Examiner, 3 June 1862, p.5.

9 Ronald Smith diary, 27 December 1907.

10 Ronald Smith diary, 28 December 1907.

11 See Nic Haygarth, Baron Bischoff: Philosopher smith and the birth of Tasmanian mining, the author, Perth, Tas, 2004.

12 PLF Collins, ‘A radioactive anomaly in central northern Tasmania (EL14/73)’, Department of Mines (Tasmania), Technical Report 18-28-31, 1973, pp.28–31.

Fascinating story and more background to my own interest in Middlesex Plain and the Vale of Belvoir. Keep up the good work.