Introduction

The last two blogs told the story of the rich copper mine at the top of Colebrook Hill. The prospect was inspected and dissected by some of the best mining men in the country. The hill seemed to be a huge deposit that would rival the Mount Lyell mine at Queenstown. Some said that it was better. The directors and shareholders of the Colebrook Prospecting Association (the Association) dreamt of building a smelting complex on the banks of the Pieman River.

In December 1907, the Association started to build a plant to smelt 200 tons a day of ore to a 50 per cent of copper matte.1 By April 1908, they had spent more than £12,000 on the furnace, a tramway, haulages, houses, a water race and machinery. Miners peeled back the skin of the hill to find rich ore for the furnace.

Smelting at Colebrook Hill

On Monday 13 April, directors, Senator John S Clemons and EM King, arrived from Launceston to witness their dream become reality.2 Maybe it was the few weeks of delays but the start of smelting was unusually low key. Perhaps it was something else. Normally miners celebrate a significant development with dignitaries by the train load, bunting, speeches, lavish meals and endless toasts to success. Not for the Colebrook smelter.

On the early morning of Monday 20 April, Cecil Rae and his furnacemen loaded the furnace with wood. The burning kindling would warm the cold heart of the furnace.3 The charge of ore and coke would have accumulated. The blowers would have fanned it to greater heat. After hours the furnace would be full and red hot. Finally, Colebrook ore was being smelted.

At 2pm, the furnace was opened for the first time. Traditionally, furnace managers would break the clay seal in the taphole with a few well directed blows. Out would have poured the yellow hot fluid. The heat scorching the faces of all the excited observers. It hissed, spat and boiled as it touched any moisture in the runners, forehearth and slag carts. Rae, the directors, the furnacemen and the curious would have seen the mixture of molten slag and matte pouring out. The slag ‘came away like so much bottle glass, indicating a low loss in copper in this direction.’ This was a very good sign.4 Matte would settle in the forehearth and be tapped regularly.

At about midnight, a leaking water jacket forced Rae to shut the furnace. In its first eight hours, it had treated 83 tons of ore. Rae estimated that it ran at a rate of about 250 tons a day. The matte was analysed as 12 percent copper, too low but this was the first smelting. The results were ‘beyond the most sanguine expectations’.5 Rae and the directors would have been happy that night.

Rae and his men would have needed a couple of days to cool, repair and prepare for the furnace for the next smelting. Matte produced on the 24 April was only 4% copper.6 On 26 April, Rae had to admit to the directors that ‘at present it is hard to get it (matte) to 10 percent’ copper. Analyses released later were 3 to 4%. 7 Some ore from the Hercules mine was also smelted.

On 4 May, shareholders were surprised by a call of 6 pence per share, especially as there was no explanation.8 The price of Colebrook shares halved over a few days.9 The Mercury speculated that smelting was not going well.

Failure

Clemons and King returned to the mine. By 6 May, the furnace had smelted 800 tons of ore over 132 hours of operation. The furnace had run for 1/3 of the time. The rate was 145 tons a day compared to the design capacity of 200. 135 tons of matte had been made. The matte averaged 8% copper, not the 50% needed.10

The directors reacted. At 4pm, Thursday 7 May, Cecil Rae broke the news to the men; ‘the smelters must be shut down, as the copper contents of the matte were not equal in value to the wages sheet’. He offered the matte to the men but if they would put it back through the furnace to increase the copper content to 35 or 40 per cent. ‘The men loyally agreed to stick to their chief’.11

The Association promised to pay the smelter-men’s wages while the matte was re-smelted.12 A week later it was clear why the smelter-men agreed. The rest of the workers, at the mine and all of the staff were immediately dismissed.13

The Association announced the shutdown and that they would call tenders for mining and sorting the ore ‘to a payable grade’. They would then run the furnace again.14

The news of the failure was a shock. Most people thought that the smelter was’ proceeding along satisfactory lines all round.’15 Many hoped that the closure was temporary.16 The share price fell again.17

A second failure

The furnace ran well. Rae took stock on 10 May. There were 90 tonnes of matte with a marginally higher copper content of 10%.18 It still wasn’t rich enough, and so the smelter-men stopped work. After running for a total of three weeks, the furnace was drained for the last time.

It was all about wages and trust. The matte wouldn’t make any money. And the Association didn’t pay the wages, despite their promise. It now emerged that the workers hadn’t been paid for 7 weeks and that they had agreed to re-run the low grade matte to try to get some of their wages back.

The workers’ ultimatum

Only weeks earlier, it was all positive. The Association had advertised for 60 men for the mine. They had come from as far as Victoria. Some were married men who had spent ‘their last shilling in reaching the district, leaving wives and families dependant in the meantime on others’. They had no money and had accumulated bills for food and board unpaid for seven weeks. They couldn’t even buy a train ticket to leave the dead smelter.

On the 12 May, the workers gave the Association ‘twenty four hours to pay in full, failing which the company be put into liquidation’.19

Sheargold’s climb

The next day, the Association’s legal manager, Edward Sheargold, arrived from Launceston. Rae, and a representative of the men, Walter Webb, met him at Colebrook siding. The workers waited at the mine at the top of Colebrook Hill.

Sheargold had to climb ‘the steep incline leading up the haulage’. He was ‘almost breathless’ when he reached the top. Between gasps he able to say that he had a fortnight’s wages. He needed a little time ‘to obtain some refreshment and recover from the stiff climb.’20

The directors were paying ‘out of their own pockets in order to try and tide over the difficulty until the balance could be paid.’ Only two of the seven weeks unpaid wages would be paid. Sheargold didn’t mention the payment was not charity or moral obligation, it was required by the Mining Companies Act.

But the workers wouldn’t even get two weeks’ pay. They had got food, board and drink with ‘orders’ as deductions from their wages. The storekeepers would get their cut first. Seven weeks pay had turned into a pittance.

Rosebery publican Dan Connolly was standing with the miners. Connolly (the brother of Thomas Connolly – the Missing Boniface in previous blogs) was a compassionate community member. He was owned a lot of money from the workers, which may not get paid. But he was prepared to forgive some of the debt to help the men. The failure of the mine hit the whole community. 21

This blow came at a bad time for the West Coast. Many mines were closed, the Zeehan smelter was shut and was ongoing unrest at the Magnet mine, that would run for at least a year. The Colebrook mine had been one bright light that was now dimmed. It took the Hercules mine with it.22

Sheargold said that the other five weeks wages would be paid ‘as soon as the company was in a position to do so.’ However, it would not come from the directors.

The men were stunned and angry. One shouted: ‘Where the deuce do you expect us to get tucker to await the pleasure of the directors?’; another called out ‘You might just as well have stayed at home as come here and pitched such a tale.’23

Webb spoke to the men calmly. Why, he asked, were the directors ‘causing misery to men and their wives and families and creating ill feeling between capital and labor (sic)’. The men voted to get legal advice about recovering the rest of their unpaid wages.

The directors view from Launceston

That night, JS Clemons chaired a meeting of the Association in Launceston.24 His position couldn’t be more virtuous. He told the press that the demands of the miners ‘was not fair to the board’. Had they not paid their legal obligation quickly?

In fact, the directors felt let down. They had been assured by the mine manager that there was plenty of good ore. They decided that low grade ore must have been processed, not the rich ore that they knew was there. The shareholders unanimously expressed ‘full confidence in the directors’.

Failure becomes a fiasco

The full extent of the failure at Colebrook became clearer with every day. The Zeehan and Dundas Herald was getting worked up. It thundered that this was the biggest failure ‘in the history of the West Coast.’ ‘The Colebrook mismanagement’ had caused ‘misery and hardships to such a large body of men’.25 About 100 to 150 men were out of work and unpaid. They were owed about £1,500 and had been offered £360 for the fortnight’s pay, before stores costs.26

According to the Herald, ‘the great Colebrook fiasco‘ was ‘practically the most astounding business that has occurred in connection with mining throughout the Commonwealth.’ It was ‘beyond comprehension’ that the directors had started the smelter without enough money to pay the men’s wages.

On Thursday 14 May;

At ten o’clock Mr E Sheargold started to dole out the mites, which a benevolent board of directors had sent him from Launceston to scatter around like seeds of kindness so as to alleviate the misery and hunger of their faithful servants, who had worked on for some seven weeks without payment of any kind under wretched conditions and, it may truly be said, without a murmur, as to their position.27

The directors ‘in their great spirit of generosity decided to pay to whom they were bound personally through law to find the first fortnight of the seven weeks due, leaving the poor unfortunate wretches who had been employed during the last five weeks to do as they best could.’

The workers were owed from £9 to £18 each. They were lucky to get a third of that. 80 men got nothing. In an act of ‘magnanimous generosity’ the directors decided to pay 10s (shillings) to any of the men who hadn’t received any money after a request from Sheargold.

With the first part of their wages paid, the men met again. This time they crowded into the smelter building and around the now cold furnace. The secretary of the Zeehan branch of the Amalgamated Miners’ Association (AMA), Steven Ford, was warmly received. ‘The sympathy of every right-thinking person on the West Coast’, he said, ‘was undoubtedly with the men’. They had been ‘treated in a most shameful manner by the directors’. The workers followed his advice to take legal action. Three representatives headed to Zeehan to get advice from the fiery Zeehan solicitor, JW Hudson.

Ford finished by offering to pay the railway ticket for anyone wanting to travel to Zeehan. The workers erupted into applause and cheers for his support, advice and generosity.

Generosity poured out of the West Coast community for the destitute men.28 The Mount Lyell mine found work for 25 men at the Iron Blow. They also got free travel on the railways to Queenstown. The Public Works Department did what it could to help.29 Men were given food and shelter and work.

It was a different story for the staff. The directors would what they were legally responsible for, and ‘that was all’. They were told to sue the Company if they wanted their pay.30

By 17 May, the Zeehan solicitor had issued 102 summonses against the Association for the unpaid wages of workers and staff.31 By then busy camp at Colebrook was deserted.”32

The next day, ‘another act of “The Great Colebrook Farce” was carried out in a quiet and orderly manner’. Rae paid out the ex gratia ten shilling payments to the 80 men in the ‘Ten Bob Brigade’. One man asked Rae ‘do you really think those poor devils of directors can spare this ten bob.’ Another wondered whether it ‘might ease many consciences to-morrow. Hope, they won’t have to go without their ‘drop of perk’ at the Launceston Club to-night.’33

Near the end of May the directors decided to avoid ‘the humiliation of a Court appearance’.34 They agreed to pay the rest of the wages in two instalments. The first was received on 1 June.35 Some men were jubilant and may ‘for once in a way, call down a blessing on the entire legal fraternity.’ The final instalment was made on 1 July.36 For the workers, the Colebrook Fiasco had wound to a close.

The future of the Colebrook mine

The Association’s energy turned back to the mine. There was a hope that the mine would get another chance. Two experts were sent to the mine. One to examine the ore body and the other to overhaul the smelters.37

In the general meeting of November 1908, the directors reported on the assessment of the mine and the smelter.38 There was the usual optimism from the board. The mine wasn’t as rich as they believed but would be payable at a slightly higher copper price. They set about raising some more money with an issue of shares. There was little interest.

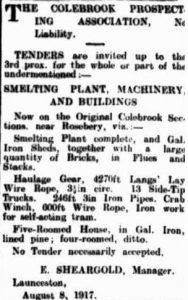

In August 1917, all the equipment at the mine was put up for sale to fund another deposit at Kooyna near Rosebery.39 About 1928, the Electrolytic Zinc Company (EZ) demolished the chimney for foundations and chimneys in the expanding townships of Rosebery and Williamsford.40 41

Just another failure?

It was far too common for mining companies to invest in expensive machinery before their ore was proved. Failure normally followed, taking shareholders money with it. The Colebrook mine was different. The Association spent years and a lot of money investigating the massive deposit on the top of Colebrook Hill. They knew that the ore would be easy to smelt because it was combined with a natural flux, there was a lot of it and the grade was good. The Association dreamed of a huge mine and smelter.

The directors believed in this dream for too long. There were warnings, but they ignored them. They believed too much in their own optimism. And almost everyone else believed them.

The result was the same, the mine failed. The directors weren’t corrupt. They lost a lot of their own money as well as others. They also caused devastation on the West Coast and for their workers.

The scattered relics of the Colebrook mine bear witness to another failed West Coast mine. The Colebrook Fiasco shows that you can’t simply wish a mine into profitability.

But who was to blame … ?

Peter Brown 2020 – copyright

1 Matte is a mixture of copper, iron and sulphur which is then refined to metallic copper, Daily Telegraph, 23 Mar. 1908.

2 Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 11 Apr 1908.

3 This description based on the starting of a very similar furnace at Mount Lyell and from personal experience, Mercury, 3 Jul 1896.

4 Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 22 Apr 1908.

5 Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 22 Apr 1908.

6 Daily Telegraph, 3 Jun 1908.

7 Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 5 Jun 1908.

8 Mercury, 6 May 1908.

9 Mercury, 7 May 1908.

10 Examiner, 30 May 1908.

11 Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 11 May 1908.

12 Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 13 May 1908.

13 Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 13 May 1908; Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 15 May 1908.

14 Mercury, 9 May 1908.

15 Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 9 May 1908.

16 Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 9 May 1908.

17 Examiner, 9 May 1908.

18 Examiner, 30 May 1908.

19 Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 13 May 1908.

20 Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 14 May 1908.

21 Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 19 May 1908.

22 Mercury 16 May 1908.

23 Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 14 May 1908.

24 Examiner, 14 May 1908.

25 Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 14 May 1908.

26 Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 14 May 1908.

27 Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 15 May 1908.

28 Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 18 May 1908.

29 Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 18 May 1908.

30 Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 16 May 1908.

31 Examiner, 18 May 1908.

32 Mercury, 17 May 1908.

33 Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 18 May 1908.

34 Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 2 Jun 1908.

35 Daily Telegraph, 2 Jun 1908.

36 Mercury, 2 Jul 1908.

37 Mercury, 9 July 1908.

38 Daily Telegraph, 30 Sept 1908.

39 Examiner, 18 Aug 1917.

40 G Jay, In the Shadow of Murchison, Advocate Printers 1993, p 58.

41 Examiner, 21 Jun 1928.