The story so far

It has been a few months since we posted about the Colebrook mine. We have told its story from the promise of a brilliant future to its reality as a sad memory.1

The Fiasco

For years, the Colebrook Prospecting Association (the Association) had proclaimed that the mine was big, full of rich copper ore, easy to mine, close to the Emu Bay Railway and its ore was self-fluxing, a metallurgist’s dream.

The Association dreamt of a smelting complex that would rival Mount Lyell’s. In early 1907, the mine manager, Thomas Williams, produced an optimistic estimate of the mine’s size, and the price of copper soared to £110 per ton. With this happy coincidence the Association decided to build a small smelter. It would have the capacity for ‘at least 4000 tons of ore per month’ and produce a matte (a mixture of copper, iron and sulphur) ‘containing about 50 per cent of copper.’2 Speculators rushed the Association’s shares. The Colebrook mine became the one bright light of hope on an otherwise depressed West Coast.

A year later, the first matte poured from the new furnace. The results were ‘beyond the most sanguine expectations’.3 The furnace settled into production. Everyone was elated.

Three weeks later, the Association’s directors shut the smelter and mine, and sacked the whole workforce. The reasons – the ore was less than 1% copper, not the 3% promised.4 And the price of copper had almost halved to return to its usual level of about £60 per ton.

Everyone was stunned. Everyday newspapers were filled with long and messy arguments. The directors of the Association were pilloried. This was the fiasco.

The Failure

Two sides formed in the battle over blame. On one was the directors, ex-mine manager Thomas Williams and their cheerleaders in the Launceston and Hobart newspapers. The Mercury said that the Association had been ‘landed in this mess’ because they relied too much on the managers at the mine.5

On the other side was the general manager, Cecil Rae, and the mine manager, Donald Finlay. They were backed by the West Coast newspaper, the Zeehan and Dundas Herald. The Herald said that the behaviour of the directors and shareholders was ‘beyond comprehension’.6

Senator John S Clemons was the Association’s most vocal director. He was well connected and a committed capitalist with a long involvement in Tasmanian mining as a shareholder and board member.7 As a politician, lawyer and businessman he was well practised at persuasion.

He quickly convinced the shareholders that the directors were faultless by blaming the managers at the mine.8 They, he said, had fed low grade ore into the furnace.9 And the matte that Rae made was too low in copper to be sold.

Cecil Rae was a young manager with a big ego. He gave a long interview to Launceston’s Examiner.

Had he ‘put through a poor grade ore and left the best?’ Rae called that ‘utter nonsense’ and said that, in suggesting it, Clemons was ‘wrong and most childish’.

Did he have much smelting experience? Yes, considerable’ he replied, ‘…the Colebrook furnace … is the fourth of the kind I have designed; all of them … giving the utmost satisfaction’. Rae blamed the low grade matte on the smelter-men not being paid and working ‘half-hearted’.

And the mine? ‘At present it is no good.’ He claimed that he had been concerned about richness of the mine before smelting started.10 The next step? ‘Oh I suppose liquidation’.11

The Zeehan and Dundas Herald backed Rae’s honesty and grit.12 Clemons disagreed. He called Rae ‘utterly incompetent’ and a liar. 13 The matte was only half as rich as Rae claimed, a pathetic 5% copper (not the 40 – 50% needed).

Clemons said that the Association had relied on Rae’s self-assured guarantee of making saleable matte to pay wages and bills. They had run out of money weeks before smelting started and waited for salvation from Rae’s matte.

The battle of the mine managers

Thomas Williams’ credentials were perfect. He was born into a family of mine managers. 14 He also spent more time at the Colebrook mine than any other manager.

He estimated the mine’s value from a ‘long series of assays … and measurements’. 15 There was 47,250 tons of ore averaging 3 percent copper.

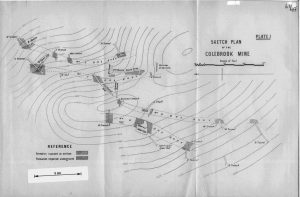

Williams opened out the deposit. He drove tunnels, sunk shafts and took assays to chase the twists and turns of the ore. He chose and developed the open cuts and stockpiled ore for the smelter.

Donald Finlay took over the mine a few months before smelting started. He had been recruited by his friend Cecil Rae because of his experience in working open cut mines. Expertise that Williams did not have. 16

Finlay had to deal with the mine as Williams had developed it. He later called Williams three open cuts A, B & C, ‘attractive to the unsophisticated’, ‘a patch of fair ore’ and ‘practically a blank’ respectively. He sorted William’s stockpiles by hand to try to increase the grade. About a quarter was dumped because it was ‘practically barren’.17 He still couldn’t get rich ore.

Faced with his own observations and tests, Finlay didn’t believe Williams’ estimate. Not that he could check the calculations because Williams had taken all his assays and measurements. Finlay pointed to a review of Williams’ sampling in 1902 that called it ‘rough and ready and likely to give misleading results.’18

Williams settled some scores. Finlay, he said, was a timekeeper who got his open cut experience from hearing the blasting at a nearby mine at Mount Lyell. For Williams’ his inexperience was obvious because he couldn’t get good ore from the Colebrook mine. Williams also turned on Rae. He claimed that Rae deliberately mismanaged the mine and smelter to damage Williams’ reputation.19

Finale

Later in 1908, two independent experts reported on the mine and smelter. The mine could be profitable at slightly higher copper prices, £65 to £70 per ton.20 Smelting failed because the engine that powered the air blower for the furnace was less than half the size needed.21

The details of the reports weren’t released and Clemons presented them with his usual optimism. The Association wanted to restart the mine. The shareholders weren’t interested.

Why did the mine fail?

The arguments and blame shifting of the directors and managers, and their supporters, were so riven with half-truths, lies and omissions that the truth seemed lost. A close look at all the evidence lets us untangle the mess.

Three major problems forced the mine to shut in May 1908. Only one meant that it never opened again.

Curious financing

Money had run out a month before the furnace was blown in. Even the normally supportive Examiner called it ‘inconceivable’ that the board had started smelting without a few months ‘money in hand’. It was ‘to put it mildly, curious financing’.22

This kind of buffer is essential because a new mine and a new plant working on untried ore would always have teething problems. A test smelting of ore in another furnace would have reduced the risk.

Poor finances helped shut the mine. However, if this was the only problem, then money could have been raised to revive it.

Mr. Rae certainly ‘melted’ a quantity of material23

Rae botched the smelting. And not because of the low copper ore. When he smelted a parcel of Hercules ore at 3.4%, he could only produce a matte of 8.9% copper.24

Rae’s fundamental failure was that he melted the ore rather than smelted it. It should have been obvious to him on the first day when the ore ran ‘through the furnace like water’. He should not have been so pleased when the slag ‘came away like so much bottle glass’.25 These were bad signs.

The wonderful self-fluxing mineral axinite in the ore melted easily. It and other unwanted minerals formed the slag. This left the iron and copper sulphides to form matte. But it was a low grade because there was much more iron in the ore than copper.

To make high grade matte most of the iron had to be driven into the slag by oxidising it. More air had to be blown into the furnace. The matte would become richer in copper. Edward Peters, the metallurgist who first smelted Mount Lyell ore, said that ‘one of the main difficulties (with semi pyritic smelting) … has always been the lack of blast (air). It requires an astonishing excess of wind.’26

Rae’s mistake also helped to close the mine. Larger engines for the blowers and a good metallurgist would fix this problem and allow it to restart.

The mine is no good

There is no doubt that low grade ore was fed to the furnace. The reason? There was very little good ore in the mine. Williams’ estimate was wildly wrong.

The expert review of the mine done in late 1908 halved Williams’ estimate of ore in reserve to 23,543 tons. The average grade was conspicuously omitted from any public reports but it was definitely lower than William’s calculation.27 Extensive drilling of the mine in the 1950s put the reserve at 12,000 tons at 1.2% copper.28

Williams made two critical mistakes. His first you’d expect from a novice prospector. He was bedazzled by the bright colours of the veins and blebs of rich ore and ignored the bulk of the duller ore around it. He tended to sample the richest ore. In his report, in 1902, a Government Geologist accepted that it was very difficult to take representative samples at this mine.29 He recommended a more rigorous method.

An experienced mining engineer should not have made Williams’ second mistake. He seemed to assume that the ore deep in the deposit was much the same as that exposed on the surface or in the tunnels and open cuts.

However, Williams should not bear all the blame. There was plenty of evidence at the time that his estimate was extravagantly optimistic.

The mine had been investigated in the late 1890s by one of the best metallurgists in the Australia, Herman Schlapp who worked with a group of BHP entrepreneurs. He spent years using the best technology to sample the mine. It proved disappointing and they abandoned it.30 The board of the Association knew this.31

The 1902 public report was clear about Williams’ poor sampling.32 It had also stated that many important assays were missing. The board made no comment about these issues.

The problems with Williams’ estimate were obvious to many before the Association decided to build the smelter. In 1907, the Daily Telegraph reminded its readers of Schlapp’s sampling and the very low copper contents.33 The paper couldn’t understand why a metallurgical engineer had not been brought in to ‘conclusively prove’ the mine.

The board caused the failure of the Colebrook mine. They wilfully ignored the many warnings. They consistently exaggerated good news and buried bad news. They knowingly spent shareholders’ money on building a smelter and developing a mine that had little chance of succeeding. There was little regard for the shareholders, workers or the west coast community.

Unfortunately, this behaviour was not uncommon during the mining booms and busts of the 19th century. The Colebrook mine remains just one example of many that dot old mining fields.

Afterwards

JS Clemons held many more directors’ jobs. One was the Tasmanian Copper Company which was to supply ore to another grand west coast failure, the Tasmanian Metals Extraction Company.

Cecil Rae moved to Malaya and matured into a well-respected engineer. Thomas Williams returned to teaching and preaching. Donald Finlay went back to Queensland mines but died a few years later in a tunnelling accident on a New South Wales railway.

The Colebrook mine is now a designated fossicking area which has produced world class samples of an interesting mineral – axinite.34

Peter Brown 2021 – copyright

1 https://mountainstories.net.au/blog/the-colebrook-fiasco-part-1-the-long-and-careful-years/

https://mountainstories.net.au/blog/the-colebrook-fiasco-part-2-the-dream-of-smelting-in-the-forest/

https://mountainstories.net.au/blog/the-colebrook-fiasco-part-3-the-fiasco/

2 Matte is a mixture of copper, iron and sulphur which is then refined to metallic copper. Tasmanian News, 12 Mar 1907.

3 Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 22 Apr 1908.

4 Mercury, 9 May 1908.

5 Mercury 21 May 1908.

6 Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 16 May 1908.

7 Clemons qualified in law and was called to the English Bar. He rowed for Oxford. He represented Tasmania in the Senate from 1901 until 1914 when he retired to England. He was an advocate of free trade and member of the Anti-Socialist and Liberal Parties.

8 Examiner, 14 May 1908.

9 Examiner, 15 May 1908.

10 Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 20 May 1908.

11 Examiner, 22 May 1908.

12 Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 26 May 1908

13 Rae was an assayer at the North Mount Lyell mine and then spent time in Western Australia and Queensland around a number of mines. Nothing in the newspapers, other than his own words, indicate that he held senior positions. He was not mentioned at the mines where he claimed to have designed or run furnaces. He went on to great success in Malaysia as a tin miner and then in the First War as an engineer in the Indian Army. He was respected in Malaysia and received the CBE (Commander of the British Empire).

14 Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 25 Dec 1896.

15 Mercury, 4 Jun 1908.

16 Donald McKenzie Wylie Finlay worked at the Mount Lyell mine for seven years and then moved to Queensland, working at the Glassford Creek Mine and Great Fitzroy Copper and Gold mine before coming to the Colebrook mine in March 1908. He returned to the Glassford Creek mine as manager and then to the Great Fitzroy mine. He was a manager on the North Coast railway near Dungog where he died on 8 March 1911 from a rock fall. Finlay was a year younger than Rae. The two likely knew each other from Melbourne and working at the same times at Mount Lyell, the Glassford mine and the Great Fitzroy mine. He was 27 when he became mine manager at Colebrook; Examiner, 13 Mar 1908; The North West Advocate and Emu Bay Times, 3 Jun 1908.

17 Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 16 May 1908.

18 Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 11 Jun 1908.

19 Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 1 Jun 1908.

20 Daily Telegraph, 18 Nov 1908.

21 Examiner, 17 Nov 1908.

22 Examiner, 16 May 1908.

23 Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 1 Jun 1908.

24 Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 5 Jun 1908.

25 Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 22 Apr 1908.

26 Edward Peters, The Practice of Copper Smelting, 1911, McGraw-Hill book company, New York, p 278

27 Examiner, 17 Nov 1908.

28 IS Gregory, Geological Report on Colebrook Prospect – SPL 302, Electrolytic Zinc Company, June 1958. Mineral Resources Tasmania – report 02 4676

29 Examiner, 15 May 1908.

30 Examiner, 15 May 1908.

31 Examiner, 1 Jun 1906.

32 Examiner, 15 May 1908.

33 Daily Telegraph, 13 Apr 1907.

34 https://www.mrt.tas.gov.au/prospecting_and_fossicking/fossicking_areas/fossicking_areas_in_tasmania/colebrook_hill_fossicking_area

I explored Mount Colebrook in the early 60’s and couldn’t find much copper there. A very poor copper deposit, but nice specimens of violet axinite as well as datolite.

There was a post office established at the mine. It was called Orrville and opened on 25.3.1898 and closed 21.3.1900 and Williams the mine manager was also the postmaster. When he left for a job in a Queensland mine the post office closed and it is speculated no-one wanted the job. There are very few circular date stamps known and they are very rare.

I thoroughly enjoyed the read of all four sections. While I am interested in the philatelic history of the area, its mining and social history as described by the author is superb in delivery and research.

Peter if you want to contact me perhaps we could have a talk about sharing images and information.

(NB I am a member of the Tasmanian Philatelic Society)

Thanks for your wonderful comments John.