Thomas James Connolly was the publican at the Rosebery Hotel, a part time prospector and active member of the small emerging mining community. Life for him, his wife Agnes and two infant daughters seemed to be going well. In March 1901, he walked to a new mining field at Barn Bluff and disappeared. Nine months later his body was found more than 25 kilometres beyond his destination. For years people who love the high country have argued about what happened to Thomas.

The question that hasn’t been answered by hours of discussions around campfires, in huts and other places was how could Thomas walk 25 kilometres along a well used track and occupied huts and not been seen or seek help. Finally, we have a plausible answer based on all the known facts and on a knowledge of the country.

Tuesday – 19th March 1901

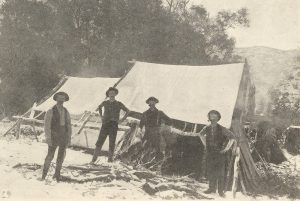

Thomas James Connolly left his Rosebery Hotel to meet miners James Swallow and Thomas Cook at their camp near Barn Bluff. He had a mineral lease at nearby Lake Windermere and had plans for Swallow’s new discovery.1

Thomas was well prepared. He wore a navy blue serge suit, cap and new water-tight boots and food and bedding wrapped in his swag.2 As well as being a publican he had been a prospector for almost 20 years. He knew the country and the weather.3 Just as he had in March 1900, Thomas followed the Mole Creek Track east.4 At Mount Farrell, he bought some supplies and stayed the night.5 Later some said that he had only enough food for a day, but he neatly recorded a list of supplies; tea, sugar, onions, a few loaves of bread and three bottles of whiskey.6

Wednesday – 20th March 1901

Thomas left Mount Farrell for Barn Bluff, steadily climbing into the high country. In the afternoon the weather turned but only brought light showers.7 Thomas probably camped for the night in one of many protected gullies near Granite Tor.8

Thursday 21st March 1901

Thomas would have crossed the high exposed alpine plains that link Granite Tor to Mount Inglis. The rain became heavier.9 It would have been uncomfortable but not dangerous. Some relief would have come when the track led him down the protected eastern flank of Mount Inglis. Soon he was back into the open on the plains around Lake Will following the regular wooden stakes that marked the track.

The track shepherded Thomas over the Bluff River, near where it rises at Lake Will, to a welcome resting place. The river tumbles over a rocky ledge to fall into a pool of water surrounded by pandani and myrtle. Out of the rain and wind, this would have been an ideal place to spend a little time to consider the journey. He could have looked across the bleak plains framed by low cloud and scudding rain showers. He may have been able to see the ridge near Lake Windermere that protected Swallow’s old camp, the tent that he had used the year before.

Nearby the rough track to the Barn Bluff camp branched off to follow a long ridge east. Thomas was expected to follow it directly to meet Swallow and Cook.10 Instead Thomas decided to go to Swallows old camp. It may have been that the Barn Bluff track was poorly marked, exposed to wind and rain and unfamiliar. It was safer to follow the well marked Mole Creek Track.

Connolly reached Lake Windermere and the old tent. It was a good campsite, shielded from the worst of the weather by the ridges to the west and north. So good that it later became home for the Lake Windermere hut.

Thomas was safe and only a few kilometres from his destination at the Barn Bluff mines. He probably arrived at Lake Windermere with plenty of daylight left in the day. Maybe the rain had cleared a little. He dropped his rolled and wet swag in the tent. Inside the swag was his food, matches and drink.11 By then he had drunk a little of his whiskey (at the time spirits were considered to fortify against cold).12 For some reason Thomas decided to make the short journey to the Barn Bluff mine camp without his swag.13 He must have thought that he had time to meet Swallow and Cook for a feed, a fire, chat and a drink. He was about to make the first of two dreadful mistakes.

Barn Bluff camp was north-east of Swallows old camp. It was a simple journey across open country – climb up to the top of the ridge on the north side of Lake Windermere and then follow it east. As Thomas walked east on the open ridge he would have descended gradually to the creek running from Lake Agnew. This glacial lake is cut into the rock of the surrounding country. It has a high rocky backwall and is ringed by pencil pine trees. Lake McRae, the source of Commonwealth Creek which runs past the Barn Bluff mining camp, could be described the same way. The two lakes were often confused. Lake McRae is just a few kilometres further east from Lake Agnew but it is obscured by a ridge until the last minute. In 1901 it was said that Lake McRae was called by some ‘Lake McCrae (sic) and by others Lake Agnew’.14

If Thomas reached Lake McRae he would have just followed the track downstream along Commonwealth Creek into forest, a deepening gorge, past Razorback Falls to the Barn Bluff camp and his mate James Swallow. Thomas made his second mistake.

It is likely that Thomas mistook Lake Agnew for Lake McRae. He followed a creek, Swallow Creek, downstream. He would have been teased by clues that he was near the Barn Bluff mine camp, like a rough track and signs of prospecting. Swallow Creek was the first mineral lease in the area.15 He would have continued down the creek.

The daylight hours dwindled but Connolly must have expected to find the camp at any time. The weather would have been kinder because he was at lower elevation and protected in the valley of Swallow Creek. There was no turning back when he worked his way down the gorge near the bottom of Swallow Creek. By now he must have known he was in the wrong place.

The walk down the valley would have been tough. A few years earlier, in 1897, a Deloraine prospector, crossed the Forth river gorge only a few kilometres further upstream. It was ‘a sheer precipitous descent, sliding over rocks, clutching at undergrowth, forcing our way through cutting grass and cabbage tree, varying this amusement by creeping on all fours through thick scrub, with occasionally a loosened boulder thundering down before us‘.16

Maybe Thomas stopped when he encountered the broad Forth River. He spent the night somewhere in the thick forest of the Forth River gorge. He would have some protection from the wind but he didn’t have a tent, swag or fire. So far Connolly would have been merely inconvenienced. Tired and battered he would have known that he could return to his tent and swag the next day.

Nature struck the final blow. The rain should have come and gone, just a band of wet weather. However, it was the early part of a blanket of polar weather. The whole state was soaked and chilled, snow was widespread. At Queenstown, they said that the rain was torrential, the wind was ‘hurricane force’ and all was bitterly cold and wet.17 In the farmland around Sheffield the rain came ‘in earnest’ on Thursday night with strong cold winds. On Friday morning the farmers and towns-people could see snow frosting the top of the Western Tiers.18 It would have settled thickly on the high plains, crowned trees with white and bowed over scrub.

Friday 22nd March 1901

Friday was going to be a tough day for Thomas. He would have shivered through the night and waited impatiently for the first weak light of the day on Friday. He was undoubtedly wet, cold, battered and tired. And all around him was snow, forest and the walls of a steep gorge. His swag was kilometres away up a long rough scrubby gorge and back into the teeth of a storm and a thick blanket of snow. There were no tracks here.19

Thomas was not beaten yet. He had one option that gave him a chance of survival, the Mole Creek Track. For years people had talked about shortcut that would take miles out of the track.20 The great geographical obstruction in this country was the Forth River gorge. It sliced though the high country and effectively blocked any road or track from going directly east to west. There was now serious talk about a track that did just that.21 But for now the Mole Creek Track went south from Lake Windermere, crossed the Forth River at the foot of the Pelion mountains and passed the Pelion Huts then made up for all the southern meandering by going north across the high exposed February Plains.

Thomas could take the shortcut by continuing east, climbing out of the Forth River gorge and striking the Mole Creek Track on the February Plains and following it to safety. Climbing up against the snow-bowed scrub must have been hard. His hands would soon be numb from cold, no help in pulling himself upwards with the bent vegetation. He would have showered himself in snow every time he grasped the bushes for purchase. It would have been a long and hard climb to reach the open plateau of the February Plains. He had to climb over 500 metres in the two kilometres to the plains.

The February Plains meant an end to the climbing but they would have been covered in a thick sheet of snow. He would have stumbled forward with his diminishing strength and energy but he still used his bushman’s skill to navigate east in this featureless and cloud shrouded white wilderness. Each step would have been a marathon, breaking through the thick snow, pausing to get his breath back before pulling his other leg out of its icy tomb to take another ponderous agonizing step. Those few kilometres to the gentle valley of Wurragarra Creek must have seemed interminable. By then he had little strength left, only enough to crawl through the snow.

Thomas probably reached the Mole Creek Track sometime on Friday. He probably crawled past it without noticing it, but in truth it was too late for it to guide him to safety. He only went a few hundred metres more. He stopped in the lee of a log in an open and grassy area.22 There is bush nearby but he hadn’t looked for shelter, he finally could go no further.23 As he lay too exhausted to move he suffered the last cruel deceit of hypothermia, he felt hot and removed some of his clothes.24

Sometime on Friday 22nd March 1901 Thomas died. The next day his body lay as a silent witness to improving weather, it was fine but cool. Sunday and Monday were ‘delightfully sunny days’, ‘all that could be desired from an autumn day’.25 The bad weather had come and gone, the worst lasted just long enough to kill Thomas James Connolly.

It was left for those still alive to carry on. Wife Agnes had two young children and a hotel to run. Brother Denis returned to mining.

It is Thomas James Connolly’s disappearance that has made him well known, but we should also remember him for what he did during his long and eventful life. He worked hard and was resourceful. He was never afraid of a failure and always supporting others in the community. A great pioneering West Coaster.

Ian Hayes and Peter Brown – copyright Mountainstories.net.au 2019

1 Bendigo Advertiser, 14 Dec 1901, p 4

2 Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 13 Dec 1901, p 4

3 Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 13 Dec 1901, p4.

4 Daily Telegraph, 16 Mar 1900.

5 North Western Advocate and Emu Bay Times, 4 Apr 1901, p 2

6 Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 1 Apr 1901; North Western Advocate and Emu Bay Times, 9 Dec 1901, p 2; the list stated gin but whiskey was found with his swag

7 Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 21 Mar 1901, p2

8 Public Works Inspector Rule found what he thought was Connolly’s tracks and his camp fire; Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 1 Apr 1901.

9 Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 1 Apr 1901.

10 Swallow and Cook did not search the old camp at Lake Windermere when Thomas was overdue. If they had they would have found his swag.

11 Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 13 Dec 1901, p 4

12 North West Advocate and Emu Bay Times, 4 Apr 1901

13 Agnes stated in August 1901 that she believed that Thomas left Swallow’s old camp ‘attempted to reach the new camp then occupied by … James Swallow … about two miles from the … old camp but that the rough and ill defined nature of the track from the … old camp to the … new camp and the severe nature of the weather then prevailing in that vicinity caused him to lose his way and that … Thomas James Connolly .. died in the bush on or about the twenty first day of March’; Tasmanian Archives and Heritage Office, Files Relating to the Administration of Intestate Estates, SC389/1/281, Agnes Connolly Statutory Declaration 6 Aug 1901.

14 Mount Lyell Standard, 17 Apr 1901.

15 George Waller, Report on the Mineral Districts of Bell Mount, Dove River, Five Mine Rise, Mount Pelion and Barn Bluff, Secretary for Mines Report 1901.

16 Daily Telegraph, 6 Feb 1897, p 6

17 Tasmanian News, 23 Mar 1901.

18 North West Post, 23 Mar 1901.

19 The Forth road and zig-zag track to the Pelion Plains was still 15 years in the future and the track to the Barn Bluff mines up the Razorback wasn’t started until February 1902.

20 Launceston Examiner, 18 Aug 1897, p 7

21 Mount Lyell Standard and Strahan Gazette, 30 Apr 1901, p 3

22 Advocate, 27 Mar 1936, p 11

23 Daily Telegraph, 9 Dec 1901, p 3

24 North Western Advocate and Emu Bay Times, 12 Dec 1901, p 3

25 North West Post, 26 Mar 1901, p2