It looks like Dr Phibes, Vincent Price’s manic Hammer horror movie character, paid Waratah a visit. Over the bank from Main Street old stamper rods poke at the sky like organ pipes rearranged by one of that madman’s solo performances.1 Further evidence of Waratah’s 150-year-old love affair with tin mining rests nearby. Rusting skips and a replica waterwheel recall Mount Bischoff’s glory days. More poignantly, perhaps, a mining trommel (a large revolving screen for sieving out large stones) has been redeployed as a tunnel in a children’s playground on Main Street. Once it was the lynchpin of Mount Bischoff’s artificial respirator, the ‘pontoon’, as it was always known locally, a last-ditch effort to revive a mine nearing exhaustion.

Mining relics in Waratah’s Main Street: (left) the trommel of the ‘pontoon’ in a children’s playground; and (right) stamper rods of the Mount Bischoff Co’s 40 Head Mill. Nic Haygarth photos.

The failing Mount Bischoff Mine during the 1920s

The Mount Bischoff Tin Mining Company, which commenced operations at Waratah in 1873, produced 62,000 tonnes of metallic tin and paid dividends of £2.5 million. However, the mine manager’s report of December 1927 was dire. The life of the mine’s payable surface deposits could be reckoned in months. With the old faces failing, the company turned to a project it had been preparing for years—working the northern slopes of Mount Bischoff and the lower Waratah River in the North Bischoff Valley. The tin ore shed by Mount Bischoff in this area had been supplemented by ore escaped from the company’s own tin dressing appliances. Government Geologist Alexander McIntosh Reid suggested that dredging the ore wouldn’t work, but a hose could be used to dislodge the ore if sufficient water pressure could be obtained.2

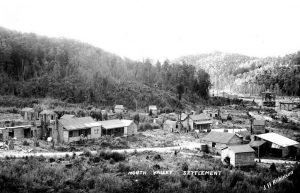

Establishing the North Bischoff settlement for its workers

The first step in establishing the North Bischoff Valley operation was to buy out the Weir’s Bischoff Surprise Mine and repair its manager’s house as the beginning of a workers’ village.3 A five-roomed home, transformer building and blacksmith’s shop were hauled in from Waratah.4 Several six-room houses with galvanised iron walls were built or trucked in. Other homes were timber.5 The problem of getting workers’ children to school in Waratah each day was solved without hiring a bus: the kids walked the shortest route, through Mount Bischoff. Each day they trudged the one-kilometre-long

main adit of the Mount Bischoff Mine on their way to and from school.

(Left) The pontoon on its pond, with the North Bischoff Valley settlement behind. Note the men rowing towards the pontoon. (Right) The view from the settlement down to the pontoon. JH Robinson photos, courtesy of the Waratah Museum, and Jeff Crowe respectively

Building the pontoon

The device installed to work the North Bischoff tin was more like a barge than a dredge. The pontoon was designed to meet the specific conditions of the boulder-strewn North Valley wash by renowned dredge builders, Thompson & Co of Castlemaine, Victoria. The 13 x 13 x 19-metre-high structure featured a 9-metre-long trommel which separated the large stones from the ore-bearing wash.6 High-pressure hydraulic hoses were used to break up the gravel and wash it down to the pontoon. It was then sucked up onto the settling floor of the pontoon and passed through the trommel, which ejected the large stones onto a conveyor belt that dumped them 25 metres behind the pontoon. The remaining gravel was washed through riffled sluice-boxes which collected the tin ore, with the detritus escaping into a tail race.7 Tin nuggets were deposited in a large steel settling box.8

Water for the hydraulic hoses was provided by a 6-km-long water-race cut from Lynch (Deep Gully) Creek, a tributary of the Arthur River.9 The pontoon was powered by a cable from the Mount Bischoff Co Power Station 3km away in the Ringtail Gully.10 A pond 2 metres deep and 16 metres square was created for the pontoon to float upon, but it would be towed to new locations via water as needed.11

(Left) Sluicing the gravel to wash ore-bearing material down to the pontoon. Note the bank of large stones at left discarded from the pontoon. (Right) Water and detritus being expelled from the pontoon in the tail race, 1928.JH Robinson and RE Smith photos respectively, courtesy of the late Nancy Gillard and Charles Smith.

Hydraulicing the northern slopes of Mount Bischoff

Today the lower northern slopes of Mount Bischoff bear the scars of multiple attacks. Collapsed 1870s/1880s adits with machinery platforms and torn boots recall early hard rock mining. Scattered early-twentieth-century Burnie Brick and Timber Co bricks and rusted 1920s sluicing pipes are heaped about picturesquely. Vehicular tracks are regrowing in the familiar spindly fashion of the slashed and burned. A concrete holding tank high up the slopes bears some responsibility for the high-pressure hose assault which has taken place below it. The ore-bearing stone and dirt washed down the slopes would have been sucked up into the pontoon for processing, leaving an eroded, deforested landscape open to the elements.

(Left) a collapsed North Bischoff Co adit. (Centre and right) The overgrown concrete

holding tank for the hydraulic sluicing.

(Below) Sluicing pipes left on the mountain side. Nic Haygarth photos.

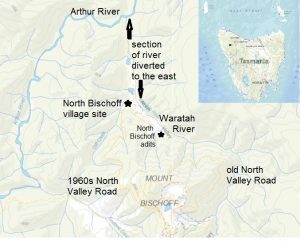

Diverting the river

One of the challenges of this work was reaching the ancient tin-bearing bed of the Waratah River—eight metres below the existing river bed. Tests had revealed that the old gravels carried payable tin to within a metre of the surface.12 The trouble was that you couldn’t work below the river bed without diverting the river, a massive job.

Details about the 2km-long river diversion are sketchy, but a steam-powered digger was probably used to create the present Waratah River channel, depositing the earth on both sides of the channel. The artificial western bank of the ‘new’ Waratah River now provides a platform for the road from the North Bischoff village site north to the Arthur River. From the road you can explore the paddocks of fine sluice box tailings left by the pontoon along the line of the original Waratah River bed.

(Left) The diverted Waratah River, looking south towards Mount Bischoff; (centre) an artificial river bank created by digging out a new water course; (right) a paddock of fine tailings from the pontoon sluice boxes along the original course of the Waratah River. Nic Haygarth photos.

The pontoon’s short, troubled career

By November 1927 the pontoon, with its iron hull and its superstructure of myrtle cut at the Mount Bischoff Co sawmill, was floating on the first pond, waiting to receive its machinery.13 By the end of the year 30 of the Bischoff mine’s 205 employees were engaged at the pontoon or diverting the river.14

It took until the winter of 1928 to get the pontoon operation running smoothly, with the motor and gravel pump operating at compatible speeds and an electric winch having been installed to lift the large stones in the wash.15 The big stones caused many breakdowns, and every time the pontoon was moved a new pond had to be blasted out.

The falling price of tin forced closure of the Mount Bischoff Mine on 22 October 1929. After recording a loss of £17,361 for the year ended 31 December 1929, the directors allowed tributers (sub-lessees who paid a proportion of their takings to the company) operate the mine from thereon.16 In 1936 the Mount Bischoff Tin Mining Co offered for sale the pontoon and superstructure, including the revolving screen (trommel) and 200-horsepower motor and a Tangye jib crane.17 The survival of the trommel as a Waratah plaything attests to the market’s lack of interest in a unique piece of engineering.

NIC HAYGARTH 2021

1 Dr Phibes was the protagonist in The abominable Dr Phibes (1971) and Dr Phibes rises again (1972), directed by Robert Fuest.

2 Alexander McIntosh Reid, ‘The alluvial and detrital ore of the Waratah River Valley’, Department of Mines Unpublished Report, 1925, pp.73–78.

3 JH Levings to the Mount Bischoff Co manager, 28 January 1927, NS911/1/34 (TAHO).

4 JH Levings to the Mount Bischoff Co manager, 8 April and 16 May 1927. The house formerly stood at the corner of Crosby and English Streets.

5 JH Levings to the Mount Bischoff Co manager, 29 April 1927.

6 Lindesay Clark to the Mount Bischoff Co manager, 18 February 1927. Consulting engineer Lindesay Clark recommended dredging, but mine manager Levings appears to have overruled him after paying a visit to Thompson & Co in Castlemaine (JH Levings to the Mount Bischoff Co manager, 23 December 1926 and 4 March 1927). Measurements for the pontoon and superstructure are from ‘Tenders’, Examiner, 12 March 1936, p.1.

7 ‘Mount Bischoff’, Mercury, 14 November 1928, p.5.

8 JH Levings to the Mount Bischoff Co manager, 21 March 1928.

9 JH Levings to the Mount Bischoff Co manager, 29 April 1927.

10 ‘Mount Bischoff’, Mercury, 14 November 1928, p.5.

11 JH Levings to the Mount Bischoff Co manager, 10 June and 23 September 1927.

12 ‘Prosperous centre’, Daily Telegraph, 7 May 1927, p.16.

13 JH Levings to the Mount Bischoff Co manager, 4 November and 16 December 1927; ‘Mount Bischoff’, Mercury, 14 November 1928, p.5.

14 Half-yearly report of the Mount Bischoff Co, 31 December 1927.

15 JH Levings to the Mount Bischoff Co manager, 7 July 1928.

16 ‘Mt Bischoff Tin Mining Co: heavy loss recorded’, Mercury, 25 February 1930, p.4.

17 ‘Tenders’, Examiner, 12 March 1936, p.1.