On 28 May 1882 a woman died on Tasmania’s West Coast and was laid to rest nearby. No doctor attended her, no police constable, magistrate or registrar was notified.1 No priest officiated at her funeral. None of these positions existed on the Heemskirk Tin Field. There was nothing but a scattered population of mostly Cornish mining managers, their five wives, some miners and children. No place called Zeehan yet existed, Waratah being the closest town. Hobart was more than 300 km away via ship or various pack-tracks.

The death of Mrs Williams, wife of Orient Tin Mine manager John Williams, received one paragraph in the Mercury, which had a correspondent on the field.2 Tasmania’s other daily newspaper, the Launceston Examiner, did not pick up the story. The fate of Mrs Williams was only ever mentioned again in the press by Con Curtain, who had been a mine manager at Heemskirk (and probably the Mercury’s resident Heemskirk correspondent) when she died. In 1896 Curtain described how Mrs Williams was taken ill, died suddenly and was buried

close to the belt of timber that skirts the present Orient farm, and when the grave was last visited it was still protected by a neat picket fence erected at the time by her sorrowing friends.3

In 1928 he updated her resting place:

close to the belt of timber on the roadside near Mayne’s farm, the plot being protected by a neat picket fence erected by her friends and relatives.4

The mystery of the sole reporter

Who was Mrs Williams? What was her Christian name, her maiden name, where had she come from? What killed her? These questions lie in the lap of Con Curtain. Given that he was the only known recorder of Mrs Williams’ death, can we even be sure that it happened? Why didn’t subsequent reporters visiting the Orient Mine mention her death or her grave? For example, if Mrs Williams was buried near the mine with a picket fence around the grave, why didn’t the Mercury’s roving correspondent Theophilus Jones mention her or her grave in his extensive report of a ministerial visit to the Orient Mine in 1883? If anything would have impressed upon government ministers the need for medical services and better communication with the West Coast it was Mrs Williams’ death.5 The pathos of the story would surely have appealed to Jones.

The clues to her identity

Without a death record or coroner’s report, the way to dig up Mrs Williams is through her husband. Mining managers called John Williams—some of them Cornishmen—were, unfortunately, a dime a dozen in the 1880s. A newspaper report about John Williams arriving on the mine site overland from Waratah in December 1881 tells us nothing about his usual place of abode, let alone his native place.6 Percy Fowler, editor of the Zeehan and Dundas Herald, told us only than that John (Jackey) Williams was of Cornish descent and pronounced the name of the mine ‘Hornet’ instead of Orient, suggesting illiteracy, a condition common among Cornish miners. 7

However, Con Curtain provided two potential clues to tracing Mrs Williams’ identity. One is a February 1883 comment that a John Williams on the Heemskirk Tin Field had posted a letter to his wife in Goldsborough, Victoria.8 The second clue was in Curtain’s 1896 recap, where he stated that John Williams’ four-year-old daughter Elsie once went missing at the mine.9

Too many Williamses

The first clue was ambiguous. If John Williams’ wife was in Goldsborough, Victoria when he posted her a letter, that suggests that either the letter was posted well before May 1882 when she died at the Orient, or that John Williams had remarried to a Victorian woman between 28 May 1882 and February 1883.

But wait—things get worse. Percy Fowler gave this chronological list of the Orient Mine managers:

- John (Jackey) Williams, a Cornishman

- John Williams

- Thomas Williams10

John Williams no.2: the wife in Goldsborough

There were two successive John Williamses! It could be John Williams no.2 who arrived at Trial Harbour on the steamer Amy in September 1882, although he was described as ‘late general manager’.11 It could also be John Williams no.2 who had the wife in Goldsborough. In fact it’s straightforward to find Cornish mining engineer John Davy/Davey Williams (1844–1925), who married Margaret Baker (1857–1911) at Goldsborough, Victoria, in 1881.12 Con Curtain claimed that this gentleman left the Orient because he missed ‘theatres and other concomitants of civilisation’.13 Williams and Baker had no child called Elsie, Eliza or Elizabeth that we know of. Barring children from previous marriages or illegitimate shenanigans, a wedding year of 1881 makes it impossible for them to have a four-year-old daughter named Elsie in 1882 anyway, making it more likely that Elsie belonged to the first John Williams.

John Williams no.1: searching for Elsie

So I need a John Williams with a daughter named Elsie and a dead wife in 1882. Given that Mrs Williams’ death was not registered and scarcely reported, the only clues to her death may be her husband’s failure to produce more children after 1882 or his remarriage to give his child/children a step-mother.

Using Ancestry.com and Libraries Tasmania’s Names Index, across the Australian colonies I found more than a dozen John Williamses with daughters called Elsie, Eliza or Elizabeth who were young girls in 1882. None of these men had a wife who was unaccounted for after 1882. In fact I couldn’t find any John Williams whose wife disappeared that year. The closest match was John Williams and Jane or Janet Reid of Chewton, Victoria. In 1882 their daughter Elizabeth Emily Reid Williams would have been about nine years old.14 The only problem is that Jane died not at Heemskirk in 1882 but at Chewton in 1881, with a death certificate to verify it.15 Did Con Curtain get his facts wrong?

The Orient moves on down the road to nowhere

Surely the Orient Tin Mining Co’s records mentioned Mrs Williams. Well, no. No condolences to her husband, not even an expression of grief calculated to shame a government that wouldn’t provide a Heemskirk road. Business as usual. By the time of its September 1882 half-yearly meeting the death of an employee’s wife was apparently just so yesterday. By then the company had taken on its third Williams (Thomas Stephens Williams of Sandhurst, Victoria) and was anticipating the arrival of its 10-head stamper battery.16 This was going to be a killer mine, the pride of Heemskirk!

Finding Mrs Williams on the ground

The Orient Tin Mine was a total flop, being abandoned in 1884 after expenditure of £11,000.17 The mine buildings remained idle until in the 1890s John Maxwell Mayne adopted them as part of a farm—Orient Farm. As we know Con Curtain stated that Mrs Williams was buried

close to the belt of timber that skirts the present Orient farm, and when the grave was last visited it was still protected by a neat picket fence erected at the time by her sorrowing friends.18

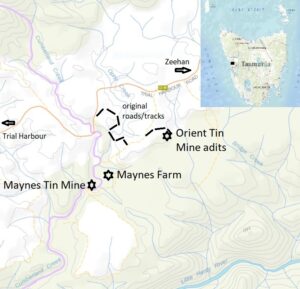

Her grave is just as elusive as her identity. Curtain later added that the belt of timber was on the roadside near Maynes Farm, but which road? The only road in 1882 would have been the old Orient Co road, not the present Trial Harbour Road. This is easy enough to trace, but no belt of timber exists along it today that might have been noteworthy in 1896 when Curtain alluded to it. The neat picket fence would have bitten the dust long ago. It would have taken just one hot fire at the Orient to raze the belt of timber, the picket fence and a wooden cross, leaving what evidence of a grave? A mound of earth, a rock cairn? There is no shortage of rockpiles at the Orient. Most of them would be chimney butts, some, perhaps, are the work of bulldozer drivers clearing paths in later mining exploration. Without summoning a trench-digger to perform an exhumation, or a medium to conduct a séance, Mrs Williams remains a phantom. Not even an ex-parrot.

Copyright Nic Haygarth 2024

1 The Heemskirk miners had established their own accident or medical fund with the intention of shipping ill or injured people to Hobart. Mrs Williams’ decline was too rapid for this contingency. See ‘Mount Heemskirk’, Mercury, 12 July 1882, p.3.

2 ‘Our Own Correspondent’, ‘Mount Heemskirk’, Mercury, 14 June 1882, p.3.

3 ‘West Coast history’, Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 25 December 1896, p.1. In my blog ‘Luke Williams and the first church on the west coast mining fields’ I stated mistakenly that the anonymous 1896 story was written by Theophilus Jones: https://nichaygarth.com/index.php/2016/12/10/luke-williams-and-the-first-church-on-the-west-coast/, accessed 9 February 2024. It is now apparent that it was written by Curtain.

4 Con Henry Curtain, ‘Old times: Heemskirk and Remine: no.23’, Examiner, 11 February 1928, p.6.

5 ‘Our Special Reporter’ (Theophilus Jones), ‘The West Coast tin mines’, Mercury, 28 May 1883, p.1.

6 ‘Tin’, Launceston Examiner, 12 December 1881, p.3; ‘Mining’, Mercury, 21 September 1882, p.2.

7 Editorial, Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 30 April 1902, p.2.

8 ‘Mount Heemskirk’, Mercury, 13 February 1883, p.3.

9 Con Henry Curtain, ‘Old times: Heemskirk and Remine: no.23’, Examiner, 11 February 1928, p.6.

10 Editorial, Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 30 April 1902, p.2.

11 ‘Mining’, Mercury, 21 September 1882, p.2.

12 Marriage registration no.3298/1881 (Victoria).

13 Con Henry Curtain, ’West Coast history’, Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 19 December 1896, p.1.

14 Born at Chewton about 1873, registration no.22697/1873 (Victoria).

15 Death registration no.6951/1881 (Victoria).

16 ‘Mining meetings’, Launceston Examiner, 29 September 1882, p.3.

17 ‘Mining meetings’, Tasmanian, 12 January 1884, p.21.

18 ‘West Coast history’, Zeehan and Dundas Herald, 25 December 1896, p.1.

very interesting, great work thanks. I’m a descendant of the Fairfield’s from the area. I have a mining survey from 1894 showing a grave in the area which could be Mrs. Williams.

Thanks Adrian for passing this on. Sorry that we didn’t get to it earlier but we had more than 250 spam messages to work through. You information has been a great help and there may be further developments. Peter

Very interesting piece of research and narrative

Interesting read and a great investigation – thanks!